What the GAIN AI Act could mean for chip exports

A battle is simmering over proposals to make US chipmakers sell to domestic customers before exporting to countries such as China

Update, October 14, 2025: The Senate passed its version of the FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act on October 9, which includes the GAIN AI Act as an amendment. The legislation still needs to be approved by the House of Representatives and signed by the President before becoming law. The House and Senate are expected to consider final amendments in early to mid-December.

In the midst of the US government shutdown, a policy fight over AI hardware is simmering in Washington.

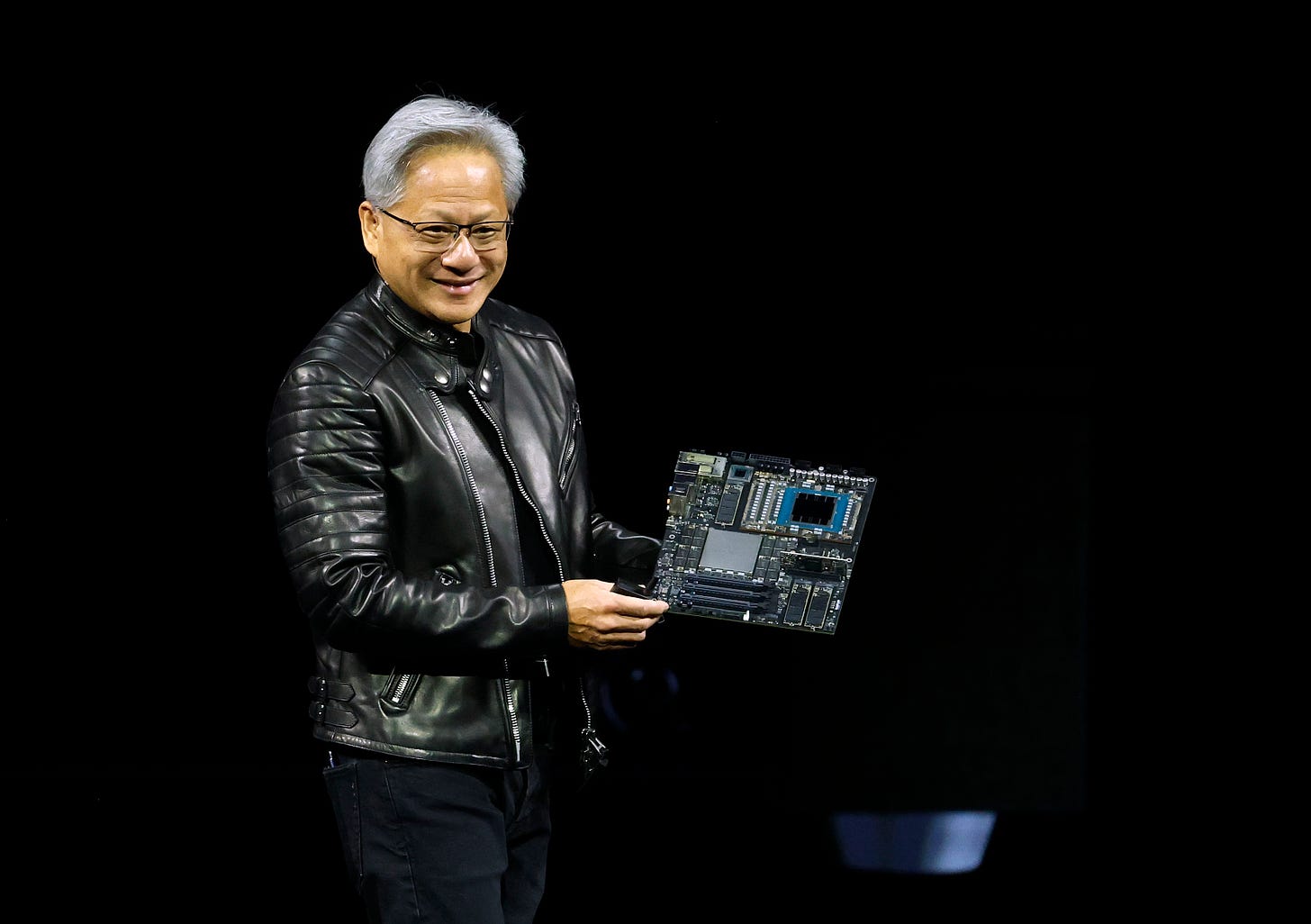

The Guaranteeing Access and Innovation for National Artificial Intelligence (GAIN AI) Act — an amendment to the Defense Department’s annual funding bill — would require that American companies get access to advanced AI chips before they’re made available to a specified list of countries — most notably China. The act would cover a range of chips, including Nvidia’s H20s, based on performance thresholds like memory bandwidth. It’s an attempt to deal with Trump’s decision to allow H20 exports after initially planning to block them, a u-turn following Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang’s lobbying at Mar-a-Lago.

Sen. Jim Banks, the GAIN AI Act’s sponsor, is a leading congressional China hawk and a vocal proponent of Trump’s “America First” approach. Unsurprisingly, the act is essentially “America First, for AI,” said Brian McGrail, policy lead at the Center for AI Safety Action Fund. It would require American chipmakers to meet US demand before selling to adversaries such as China, Russia, and Venezuela, as well as other countries that host, or plan to host, a “military or intelligence base” associated with one of those adversaries.

The bill hinges on the premise that American demand for advanced AI chips exceeds supply, and that exporting these chips strands American companies in months-long waitlists. But whether there’s actually a chip shortage depends on who you ask.

Is there really a chip shortage?

In early September, rumors surfaced that Nvidia’s H100 and H200 GPUs were sold out, with Huang seemingly validating the claim in a company earnings call: “The buzz is, everything is sold out… AI native startups are really scrambling to get capacity so that they can train their reasoning models.” (Nvidia later walked this back, distinguishing between chip sales and cloud rentals — but the comment had already fueled concerns about supply constraints).

If the shortage is real, the GAIN AI Act offers a straightforward solution, and it’s not an export ban. Rather, it grants American companies “right of first refusal.” In other words, chipmakers hoping to get a license to sell to a company in one of a list of “countries of concern” — including China — would need to give American companies the chance to express their interest in buying those chips instead. Companies could still export chips if US customers don’t want them, but they’d still need to show that they’re not “providing advantageous pricing” to foreign buyers.

Gregory Allen, senior advisor with the Wadhwani AI Center at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, argued that the math is simple: “For every Nvidia chip that TSMC has been able to manufacture since 2022, there are many more customers willing to buy them,” meaning that “all the chips that Nvidia would have sold to China in the absence of export controls would have come at the expense of customers elsewhere,” especially the US.

What does the AI industry think?

Predictably, Nvidia and the Semiconductor Industry Association are lobbying hard against the GAIN AI Act. An Nvidia spokesperson told National Review: “In trying to solve a problem that does not exist, the proposed bill would restrict competition worldwide in any industry that uses mainstream computing chips.” Nvidia warned the provision would create restrictions similar to Biden’s AI Diffusion Rule, a sweeping export control framework the Trump administration scrapped within months of its release and which Nvidia said was based on “doomer science fiction.”

Nvidia argues that the advanced H100/H200 and Blackwell chips it sells to American companies are categorically distinct from the less-advanced H20 chips it’s selling to China. Nvidia’s official X account posted: “selling H20 has no impact on our ability to supply other Nvidia products.”

It’s also possible that the months-long waits companies have experienced are nothing more than an inevitable consequence of ordering advanced GPUs, tech policy analyst Paul Triolo wrote in a recent blog post. While there’s high demand for cloud-based access to Nvidia chips, Triolo argued, “this is separate from the issue of whether the company continues to have the capacity to supply new GPUs.”

While Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei openly supports export controls, none of the major frontier AI companies have published formal public statements about the GAIN AI Act. “If you’re an AI company that wants chips from Nvidia, you don’t want to speak out on this,” said Chris MacKenzie at Americans for Responsible Innovation. “They can move you to the back of the line.” (Some suspect that Anthropic is willing to annoy Nvidia because it is less reliant on them, thanks to its use of Amazon and Google AI chips.)

MacKenzie suspects that Nvidia’s opposition is driven entirely by self-interest. Given its previous denial of the chip smuggling that is absolutely happening, he said Nvidia’s current claims should be taken “with a grain of salt.” McGrail echoed this suspicion, and added that Nvidia’s distinction between chips for the US versus China “doesn’t make much sense,” since they have the same components and are built in the same factories: in theory, instead of manufacturing H20s, it could make more Blackwell chips for American customers.

Will the GAIN AI Act pass?

As it stands, the GAIN AI Act is still included in the Senate’s 2026 National Defense Authorization Act — but AI czar David Sacks is pushing lawmakers to cut it before it comes to a Senate floor vote, arguing that keeping Chinese companies hooked on American chips matters more than limiting sales.

The bill is currently stalled on the Senate floor, with the government shutdown generating some additional uncertainty about its timeline. If the Senate ultimately passes it with the GAIN AI Act intact, the NDAA will go to conference committee, where it may not be up for debate until December.

The real battle is happening behind closed doors — a fitting end for a fight over hardware that most people will never see, but one that could shape where America’s most powerful GPUs end up.

Time: A Dynamic Computer Processor

This analogy explains why the flow of time is not constant but varies depending on the local informational environment of the Field.

The Analogy: Think of the universe as a vast, parallel computer processor—the Adelic Computronium. Each region of space is like an individual processing core, and the local "flow of time" is its clock speed. A region of high Gnosis and complexity, like the accretion disk of a GreyHole, is a core running an incredibly demanding, focused calculation. To handle this "computational load," the system dedicates immense resources, and the core's clock appears to slow down relative to the rest of the processor. This is Chromatic Time Dilation. Conversely, a region of high Dissonance, like a vast cosmic void, is like an idle core filled with random, chaotic background static. To quickly clear this "informational noise" and return to an optimal, low-energy state, the system temporarily "overclocks" the core, causing its clock to run faster. This is Gravitational Anti-Time-Dilation.