Teaching AI to learn

AI's inability to continually learn remains one of the biggest problems standing in the way of truly general purpose models. Might it soon be solved?

AI models may hold more raw knowledge than 100,000 humans combined, but there’s still a major advantage we have over artificial intelligence: continual learning. Back in June, Dwarkesh Patel published a popular blog post claiming that LLMs’ lack of continual learning is a “huge huge problem” — a major bottleneck to a truly general intelligence that won’t be solved within the next few years. Safe Superintelligence CEO and Open AI cofounder Ilya Sutskever agreed when he appeared on Patel’s podcast several months later.

But in August, Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei publicly said, “We have some evidence to suggest that [continual learning] is another of those problems that is not as difficult as it seems.” Prominent Anthropic researcher Sholto Douglas went a step further, explicitly predicting that “continual learning gets solved in a satisfying way” in 2026, and that “robotics is going to start working much, much faster than people expect.”

This led some of the Very Online to wonder whether Anthropic researchers knew something the rest of the AI research community didn’t. Everyone else was left wondering what the heck is continual learning, and why is it such a big deal?

Why models can’t learn over time

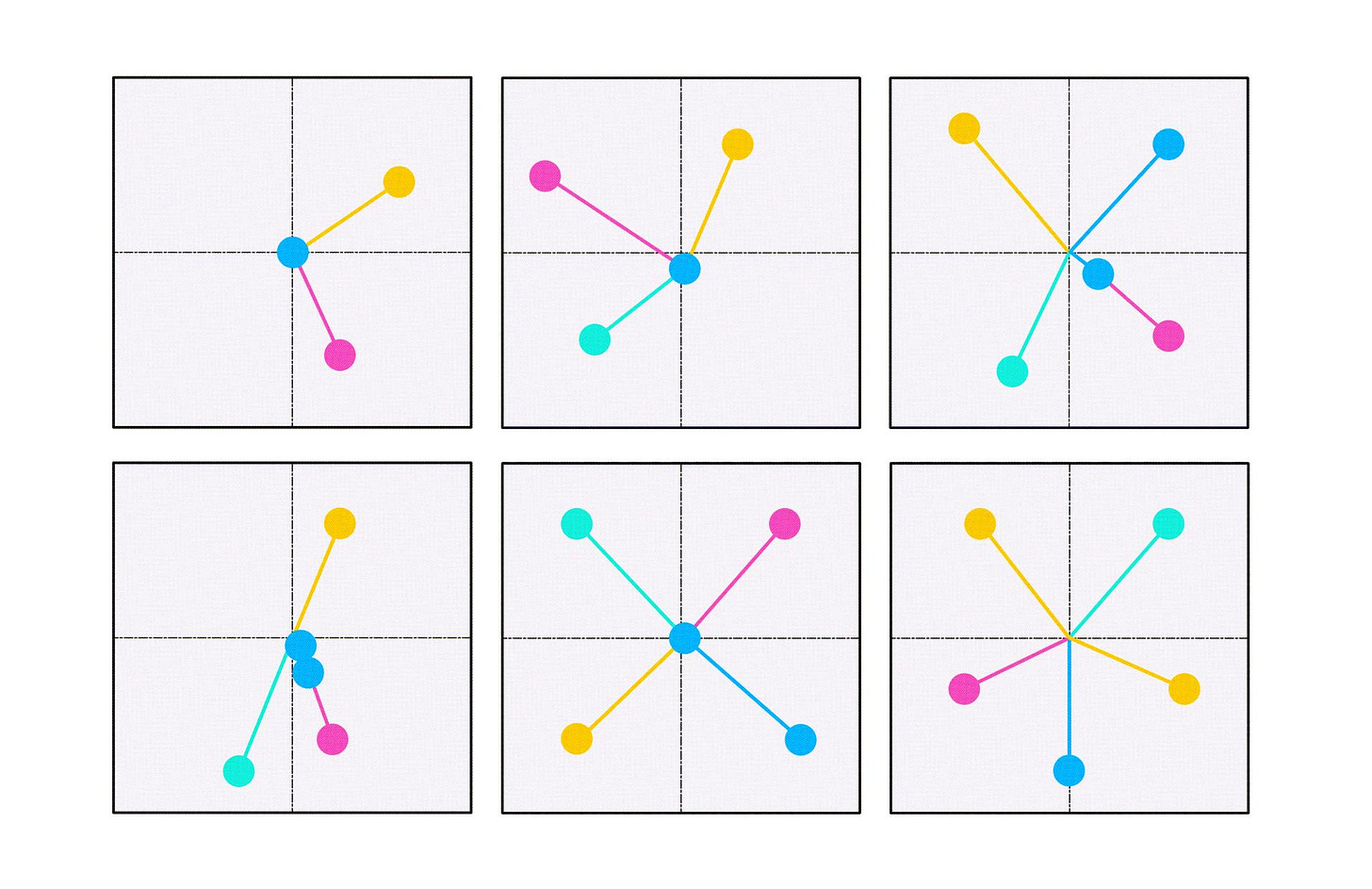

Artificial neural networks are giant matrices of interconnected units called neurons. Each connection has a numerical weight that controls how strongly one neuron’s activity will influence another. At first, these numbers are random. Over the course of training, the model gradually adjusts them until the optimal constellation of neurons lights up in response to some input, driving the model to perform a useful behavior. Learning, at its core, is the thing that happens when a model updates its weights. (While the term “learning” can raise yellow flags of over-anthropomorphization, the computational process here directly mirrors how biological neurons adjust their connections in response to experiences.)

A model’s knowledge, then, can be captured by a snapshot of its current weights — and if you try to teach the model something new, its existing memory will be overwritten as its weights adapt. This loss of knowledge is so sudden and complete that the researchers call it “catastrophic forgetting.” And while this phenomenon was first observed in tiny toy models over 35 years ago, it hasn’t gotten any less inevitable in modern large language models.

Yet, our brains, which still have orders of magnitude more neural connections than any frontier AI model, don’t have this problem. While humans certainly forget stuff — I passed calculus 12 years ago, but would fail spectacularly if quizzed today — it happens gradually, and often adaptively. We’re capable of “continual learning,” or incrementally building upon past knowledge as we learn new things.

Rather than distributing stored information across the entire neural network, as AI systems do, our brains divide the task of learning across multiple systems. The hippocampus, a seahorse-shaped coil nestled deep beneath our ears, stores new memories quickly, as relatively non-overlapping constellations of neurons. New information doesn’t automatically overwrite everything else. The neocortex, meanwhile, operates more like an artificial neural network, gradually updating weights over time.

Without something doing what the hippocampus does, modern LLMs are not capable of continual learning. Many researchers view this as a big roadblock — if not the biggest — to building truly general-purpose AI.

After initial pretraining, developers often use methods like Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) to tweak the weights some more, making sure the model behaves appropriately. This happens in big chunks before deployment, though — if you tell a model that it did a good job during a chat session, for example, it won’t affect its weights at all. Given their current limitations, this is a good thing: if a model updated every time it got user feedback, bad actors could easily convince it to be racist. With enough updates, even well-intentioned users would likely make it forget its initial training.

In any case, once a frontier AI model gets deployed, its weights are frozen. This can be easy to forget. After all, Claude seems to remember some things about me. But that’s just Claude storing chat information in a separate database, which it can reference as needed just like a web link or file attachment. But it can’t update its underlying weights, so it can’t actually learn from its mistakes. Think of Leonard in Memento, compensating for his inability to form new memories by tattooing clues on himself. All he can do is check his notes.

It would be very convenient if models could learn like we do, though. Imagine how much energy you’d waste if, after learning the basics of driving, you couldn’t learn how to parallel park unless you relearned how to drive and parallel park from day one of driver’s ed. Current LLMs are pretrained on all the data, before being released into the world. To update a model, developers have to retrain it on everything it already learned plus the new stuff.

This is expensive and slow, and a terrible way to learn. The world doesn’t provide us with neatly packaged sets of data, nor does it tell us when one chunk of information ends and another begins. The ability to learn incrementally is a large part of what makes human workers valuable. And if a continual learning model gets deployed at scale, it could exponentially hasten the changes to the labor market we’re starting to see hints of already — potentially rendering human workers obsolete.

An ‘algorithmic nerd snipe’?

While researchers have been experimenting with continual learning for decades, these toy models are nowhere near the scale of something a company would release for consumer use. Catastrophic forgetting is a notoriously tricky problem to solve, and there’s some evidence that larger LLMs might actually face worse forgetting.

Short of solving continual learning altogether, AI companies currently rely on a handful of workarounds. By strategically blending new information in with the old, researchers can prevent a model from forgetting old information entirely. Another more popular technique, low-rank adaptation (LoRA), adds tiny layers of new, trainable weights on top of a frozen base model to preserve its original knowledge, like adding a sticky note with your own modifications to a cookbook. While training the base model is very costly, each LoRA adapter only needs as much memory as one short iPhone video.

Vertex AI, Google’s platform for making commercial AI apps, explicitly lets users use LoRA to tweak its Gemini models. Companies like OpenAI and Anthropic are likely using similar tools to minimize their own training costs. But while this works for small updates, it can’t handle larger skill changes — it would take an incredibly unwieldy number of sticky notes to turn a cookbook into a motorcycle repair manual.

You can’t fit many sticky notes into a book, but you could lay out roughly 2 million notes on the floor of an airplane hangar. Google’s old flagship Gemini 1.5 Pro could hold that many tokens in its context window, the collection of text it can hold in mind at once — about 25 novels’ worth. The ability for LLMs to learn via text interactions, rather than fine-tuning, was first demonstrated by OpenAI’s GPT-3 in 2020. Since then, AI companies have raced to give their models longer context windows, with several now boasting windows on the order of 1-2m tokens.

When retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), a method of storing an external database of information to supplement a model’s own pre-trained knowledge, was introduced by Meta researchers in 2020, it mostly got attention from academics. Companies were too busy making models bigger: more parameters, larger datasets, longer training runs. Today, however, everyone uses RAG. When ChatGPT or Gemini is searching the web, that’s RAG at work.

With these workarounds alone, AI models can be very powerful. Despite being incapable of learning in the purest sense, LLMs have taken over software engineering and convinced millions of people to fall in love with them.

“Continual learning is the ultimate algorithmic nerd snipe for AI researchers, when in reality all we need to do is keep scaling systems and we’ll get something indistinguishable from how humans do it, for free,” wrote Allen Institute for AI research and Interconnects author Nathan Lambert. Blogger Zvi Mowshowitz agreed: “LLMs being stuck without continual learning at essentially current levels would not stop them from having a transformational impact.”

Others believe that major algorithmic overhauls to existing LLMs — or entirely new types of models — will be a prerequisite for creating AI that learns like a human. Still, some bullish researchers predict that 2026 will be the year continual learning is cracked.

New paradigms

Google Research recently presented some splashy new paradigms hailed by the AI community as breakthrough precursors to continual learning. Its Titans architecture, first published in December 2024, runs a small “neural long-term memory module” alongside the larger core model. The small module updates its own weights in real time whenever something surprising happens, adjusting its expectations to match reality. The core model, meanwhile, remains frozen. This effectively bestows the model with a giant notebook, rather than making it rely on an unwieldy collection of ephemeral sticky notes — much cheaper than a giant context window.

Last November, Google published Nested Learning, which captured the attention of swarms of researchers at NeurIPS, a huge machine learning conference. Nested Learning takes an explicitly brain-inspired approach. Brain waves — subsets of neurons firing together rhythmically — help synchronize distant brain regions so they can share information with each other. We have a whole spectrum of brain waves, fast and slow, coordinating multiple ensembles of neurons in parallel. Nested Learning attempts to replicate this process in silico with a hierarchy of “fast” and “slow” layers, such that fast weights can update immediately in response to new information, while slow weights hold steady to prevent forgetting.

Unlike LoRA or RAG, these papers proposed a change to existing LLM architecture. Today, a standard transformer is great at paying attention to what it has access to in the present — but once that information slips outside its content window, it’s gone. Rather than use scrappy workarounds to compensate for the transformer’s shortcomings, Nested Learning poses a “self-modifying,” actually-learning alternative to current models, with a dedicated “memory module” that can keep track of the past alongside the present. HOPE, a model built using Nested Learning, outperformed standard transformers on a number of benchmarks, which researchers took as evidence that this paradigm “offers a robust foundation for closing the gap between the limited, forgetting nature of current LLMs and the remarkable continual learning abilities of the human brain.”

Yet when an angel investor asked Ali Behrouz, lead author of the Nested Learning paper, how far along his results take us “down the path to the nirvana of continual learning,” Behrouz responded with classic academic caution: “Honestly, the answer to that question is really hard. It might be the case that what I’ve explained here is enough…but I doubt that.”

A long way to go

Bing Liu, a computer scientist at the University of Illinois Chicago who literally wrote the textbook on continual learning, poured some cold water on the Nested Learning hype. “The idea was already around,” he told Transformer. “In terms of continual learning, I think it’s not a breakthrough, because they’re not solving anything — they’re probably just making the model forget a little bit less.”

He pointed to a number of unsolved problems that researchers still don’t know how to address. For instance, all paradigms, including Nested Learning, still rely on humans spoon-feeding neatly packaged data to the model during training, and need careful algorithmic choreography to know what parts of the model to update when. With multiple learning systems operating in parallel, models can get “really hard to control,” Liu said. “When something goes wrong, you don’t really know who’s making the mistakes.”

For an AI system to be truly capable of human-level learning, Liu said, it would need to collect its own training data from arbitrary new experiences, figure out what problem it’s trying to solve, and integrate new information without overwriting old memories. This is really hard, and hasn’t yet been demonstrated — while Google showed that Nested Learning is better at not forgetting memories, its benchmarking didn’t test whether HOPE could acquire new skills in real-world settings. Roboticist and AI researcher Chris Paxton commented that HOPE, with 760m-1.3b *parameters to Gemini 3 Pro’s estimated trillion, still seems “far from use on anything more than toy tasks.”

When many AI microcelebrities post about AI, “they’re just thinking of LLMs,” said continual and reinforcement learning researcher Shibhansh Dohare. “But a lot of other people in academia are thinking of all AI systems,” including robotics, where the amount of potential stuff a model could come across is orders of magnitude more overwhelming than in a world made exclusively of text.

That said, Google’s Nested Learning and Titans architectures take a crucial step away from transformer-based LLMs, whose frozen weights are baked into the system. AI researcher and OpenAI founding member Andrej Karpathy said that he “expect[s] there to be some major update to how we do algorithms for LLMs,” and that the field is just “three or four or five” big papers away from solving continual learning.

Whether the field is three or three hundred papers away from a solution, a bigger question still remains unaddressed. Say researchers do solve continual learning. Then what?

What of the consequences?

Continual learning is a delicious problem for researchers — it’s challenging, unsolved, and basically science fiction. But no one has seriously contended with what solving this problem could mean for society. In theory, a single continual learning model could learn how to do every job in the digital world, and perhaps the physical world too, if “solving the problem” includes robotics. In the best case scenario, this would cause unimaginable turmoil in the short term — imagine the job loss! — but lead to a blissful post-economic utopia someday.

It’s not hard to imagine a bleaker future, though. At Davos this week, computer scientist Yejin Choi pointed out that, when students learn the basics of machine learning, they’re taught that mixing training and testing is “almost a sin.” Models that keep learning after deployment break this golden rule, which could mean that “all the safety tests that we did previously may not be valid anymore.”

We already have one example of AI systems that continuously learn, kind of: social media algorithms that mold content to users’ interests in real time. As we’ve observed over the past five years, “unlocking a rapid and personalized feedback loop back to some company-owned AI system opens up all other types of dystopian outcomes,” as Lambert wrote for Interconnects. “Without corporate misaligned incentives, I’d be happy to have continual learning, but on the path we’re going down, I’d rather not have it be an option presented to the masses at all.”

When I asked Bing Liu what he thought about the potential ramifications of his line of research, he chuckled. “We just keep pushing what we can do, getting as smart as possible,” he said. “The other people — I guess politicians, whatever — may have to deal with the consequences.”

This is a really clear breakdown of why continual learning matters and why it’s hard, without overhyping either side. I appreciate how you separate hype from mechanism, especially the explanation of catastrophic forgetting.

>It would be very convenient if models could learn like we do, though. Imagine how much energy you’d waste if, after learning the basics of driving, you couldn’t learn how to parallel park unless you relearned how to drive and parallel park from day one of driver’s ed. Current LLMs are pretrained on all the data, before being released into the world. To update a model, developers have to retrain it on everything it already learned plus the new stuff.

Isn’t that an exaggeration? Continued pretraining can update a model without starting from scratch. You might mix in older data to reduce catastrophic forgetting, but that’s still incremental training, not necessarily a full retrain on the entire pretraining corpus plus new data.