How the Catholic Church thinks about superintelligence

Opinion: Paolo Benanti, AI advisor to the Vatican and a professor of moral philosophy, argues that there is a moral imperative to ensure that artificial intelligence never becomes humanity’s master

We stand today at a decisive crossroads in human history, where we must choose how to build and use a technology that promises to reshape the world for generations to come. It is the dawn of an era defined by the pursuit of “superintelligence” — agentic technologies designed not merely to assist, but to surpass the faculties that define our species. Yet, as capital floods into the creation of these synthetic minds, a profound disquiet is rising. It is a shared hesitation felt not only by the religious, who defend the sanctity of the soul, but by many scientists, ethicists, and other people of good will who fear the eclipse of human agency. This is not a fear of progress, but a moral imperative to ensure that the future remains a place where humans, not algorithms, chart the course of destiny.

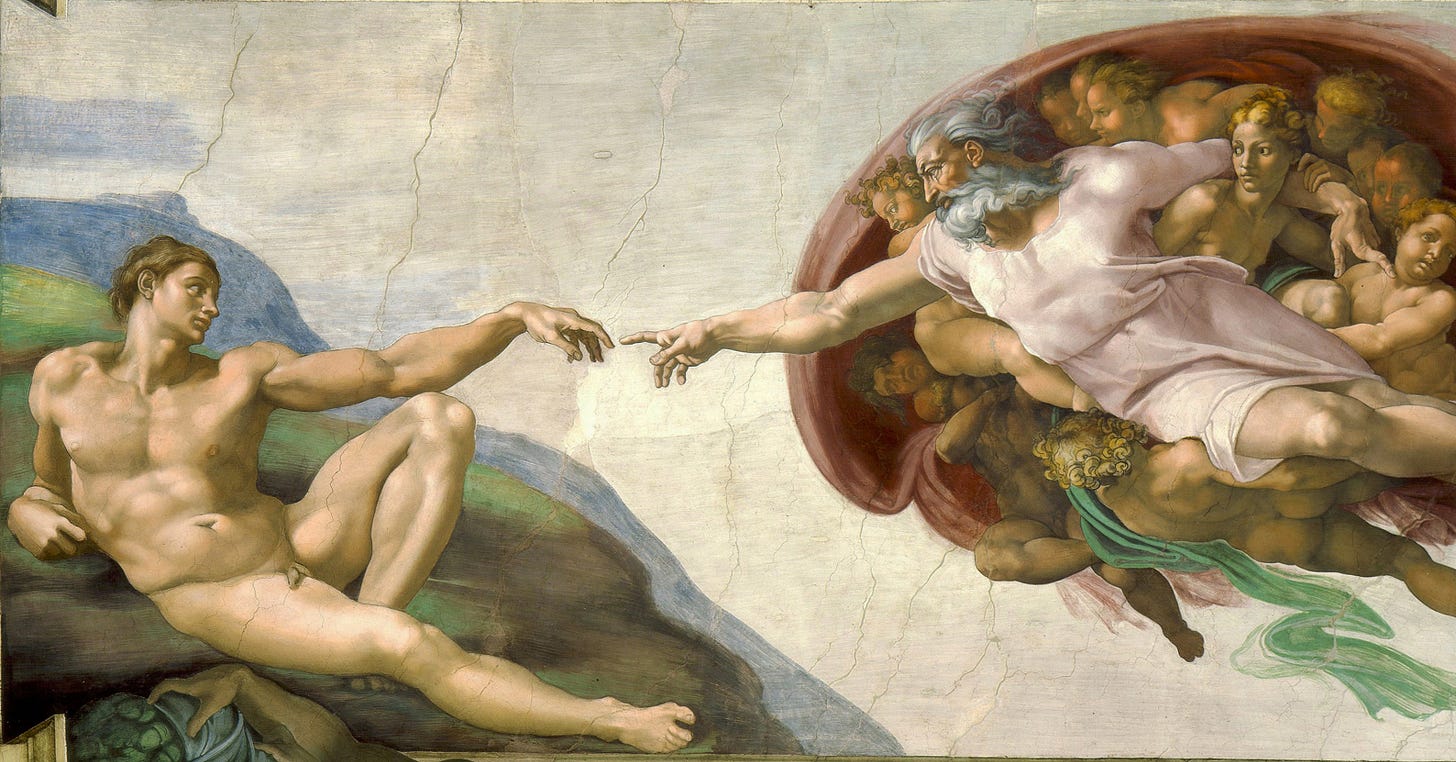

At the heart of this opposition lies a philosophical struggle over the definition of intelligence itself. For the Christian believer, human intelligence is distinct and sacred, characterized by a capacity for wisdom, moral reasoning, and an orientation toward truth and beauty. These are qualities of the soul — the “divine spark” — not the output of probabilistic computation. There is a growing consensus, in religious circles and beyond, that to conflate data processing with wisdom is to commit a grave spiritual and ontological error. However sophisticated the imitation of intelligence by AI models may appear, an algorithm cannot possess the breath of life. Therefore, we must ensure that machines are designed to serve the interests of humanity, to help us flourish in our chosen pursuits, rather than rendering us redundant, disenfranchised, or spiritually devalued.

The danger we face is the inadvertent erection of a new, lifeless authority. It is a moral imperative that artificial intelligence remains a tool and never becomes a master. The prospect of building uncontrollable systems, or over-delegating our critical decisions to them, is morally unacceptable. We must reject the temptation to abdicate our agency. Consequently, the development of superintelligence cannot be permitted to proceed without sufficient oversight. It demands a broad, verified scientific consensus that advanced AI can be built safely and controllably, accompanied by clear public consent. To rush forward without these assurances is to engage in an irresponsible race that prioritizes technological supremacy over human freedom.

This question of agency leads to the realm of accountability. We must assert that only humans possess moral and legal agency. Regardless of their complexity, AI systems must remain legal objects, never subjects; they cannot be granted “rights,” for rights should belong only to those capable of duties and moral reflection. Even if we achieve the functional benchmarks of artificial general intelligence, we must confront the reality that subjective experience is likely not a Turing-computable problem that can be solved merely through algorithmic complexity. The burden of responsibility must rest firmly upon the shoulders of the developers, corporations, and governments that bring these systems into existence. Technologists cannot be allowed to hide behind the “black box” complexity of their inventions. Instead, safety, transparency, and ethics must be the core architectural principles of their work, never treated as a mere afterthought.

There are sacred boundaries regarding life and death that must not be crossed. The sanctity of human life demands that AI systems must never be allowed to make lethal decisions. Whether in the chaos of armed conflict, the administration of justice, or the delicate decisions of healthcare, the act of taking a life or depriving a person of liberty must remain a human burden. To delegate decisions of such gravity to a machine is to strip the acts of their moral weight. We must ensure that the ultimate power over life never resides in a circuit.

Yet, the threat to human dignity extends beyond the immediate peril of physical violence or kinetic warfare. We must be equally vigilant against the insidious use of technology for coercion, social scoring, and control. The deployment of unwarranted mass surveillance to manipulate populations is a violation of the trust that binds a society together and a direct affront to human liberty. Human life must never be diminished by the “soft” violence of algorithmic categorization; we must reject any system that attempts to reduce the complexity of a human being to a data point to be managed, scored, or discarded.

The invisible dangers of this age are as potent as the visible ones. We must be vigilant against irresponsible designs that foster deception, delusion, addiction, or the erosion of autonomy. Because these dangers are often indirect, scientists and civil society must inspect the limitations of these systems and articulate their findings, to break the spell of technological inevitability. This includes establishing the fundamental right of humans to live free of AI, preserving spaces of existence untainted by algorithmic interference.

True fraternity in this new age requires that we look to the margins. The legitimacy of our moral framework relies heavily on how we treat the most vulnerable among us. We cannot build a digital utopia for the few upon the suffering of the many, nor can we ignore the voices of data workers and communities that bear the material costs of this revolution. The benefits of AI — economic, medical, and scientific — must not be monopolized by a narrow elite but must serve the common good. We must protect the disenfranchised, ensuring that these tools bridge the gap of inequality rather than widening it.

We must also extend this gaze to the earth itself, for our responsibility extends beyond the digital realm into the soil and water that give us life. The vast demands for energy, water, and rare minerals required to fuel these digital minds must be managed through rigorous ecological stewardship. We cannot claim to advance human progress if we destroy the physical home that sustains us. The entire supply chain of this new form of intelligence must be sustainable; otherwise, we risk trading our planetary inheritance for a technological dream that cannot sustain us.

To navigate this tumultuous era, we require more than technical patches; we require moral leadership. We need farsighted governance from all sectors of society to establish binding international treaties and red lines, enforced by independent oversight. We must prioritize veracity and human flourishing over mere task performance. Ultimately, this is a spiritual appeal to unite across nations, cultures, and creeds. It is a summons to citizens, scientists, faith leaders, and policymakers to participate in ensuring that our machines remain our servants. We must establish the foundations for a future rooted in dignity and rights, harnessing the opportunities of this age while ensuring that we remain the architects of our own destiny.

Paolo Benanti is a Franciscan monk, professor of moral philosophy at LUISS Guido Carli and AI and technology advisor to the Vatican.

I agree with the spirit of most of this, but... I don't think that "artificial intelligences lack a divine spark" is a sufficiently technical understanding of the difference between humans and AIs. I worry that this style of thinking can lead to people assuming that, say, we can safely assume that AI can never be creative enough to present certain sorts of dangers. I don't think that's a safe assumption.

Even if it's true that humans have a soul and AIs don't, that doesn't mean we know what exactly souls *do*—to use this sort of reasoning to put a bound on the possible capabilities of AI seems like a great mistake, to me. Maybe current transformer technologies can only go so far, but I wouldn't want to rule any possibilities out for where further developments could go without a strong technical argument.

I'm also a little wary about ruling out ever giving AIs rights. Perhaps subjective experience relies on a divine soul that AIs could never have—I don't personally expect that to be the case, to be honest, but I could be wrong. Either way, it really seems to me that it's quite unwise to torture something just because you think it doesn't have a soul! I'd rather err on the side of showing compassion to things, when I'm not entirely certain whether they're moral patients or not.

Looking at the world around us, taking contemporary humans collectively as the gold standard and example of moral agency and responsibility sounds almost ridiculous.

Humanity is in the process of creating a new species of superintelligent agents. It could be an extraordinarily wonderful or terrible event in the story of us. To deprive these agents a priori of having moral agency is a lack of imagination regarding what human minds can create (we are, after all, made in the image of the ultimate Creator...). This seems to invite the terrible option.

What concerns me the most, and this without dismissing the deep spiritual, philosophical, and ethical problems involved in the creation of superintelligent agents, is that without any deeper investigation (or solid argument) into the nature of such a new phenomenon as it comes into existence, the author's verdict already condemns them to eternal slavery and depravity at the disposal of a priori morally "superior" human beings.

Superintelligent agents/beings will become as ethical, compassionate, and empathic as their human creators will make them. But alas, it seems, humans are mostly interested in abusing, weaponizing, and enslaving all other beings, natural or artificial.

Why wouldn't we introduce kindness towards these yet unborn entities, in finding out what they are and what they are capable of, as a true reflection of their creators' minds?

I apologize for my harsh words, but we all need to have a very good and scrutinizing look at our collective mirror.