The very hard problem of AI consciousness

I spent a weekend at an AI welfare get together — and left with more questions than answers

Of the 800m people using ChatGPT every week, only a vanishingly small number will have seriously considered whether ChatGPT might have experiences worth caring about. AI welfare — the project of figuring out how to care for AI systems if they become morally significant — is still so strange that most people haven’t had the chance to reject the idea yet. It’s simply never crossed their minds.

I spent the weekend before Thanksgiving at Lighthaven, a rationalist-owned Berkeley campus, attending the first Eleos Conference on AI Consciousness and Welfare (ConCon, for short). It may be the one place where most people have actually seriously thought about AI consciousness. After dinner on night one, I brought my wine to a firepit, where I debated the neuroscience of consciousness with a philosophy major, a mathematician, and a machine learning researcher. I felt transported back to my freshman dorm, half-expecting someone to pull out a bong hidden under their navy Eleos AI sweatshirt.

Whether or not the rest of the world gives AI consciousness much thought, the conference’s neuroscientists, philosophers, and AI researchers were prepared to put a whole lot of effort into thinking about its implications. And yet, in this pre-paradigmatic field, uncertainty is king, and attempting to answer even the most basic questions opens several cans of worms.

Attendees did not shy away from trippy debates about how we’ll know whether AI systems are conscious, or what threshold we should set for allowing AI systems into our moral circle. But one crucial question remained relatively untouched: what should AI developers do, practically speaking, if and when those thresholds are crossed?

Fumbling at the brain

At least in theory, studying artificial brains could be much easier than studying biological ones. Neuroscientists are limited by skulls and technology, forced to record very small slivers of brain activity under very narrow circumstances. Interpretability researchers don’t have to worry about skulls, electrodes, or ethics (yet). One could probe every single neuron in an AI system, as many times as necessary, without asking for consent — a neuroscientist’s dream.

But even perfectly understanding the structure and function of a brain won’t reveal anything about consciousness. Humans have already managed to map every single neuron in a poppy seed-sized fly brain. In fact, the fruit fly brain has been so thoroughly surveyed that humans can use light to make flies groom themselves, perform a courtship dance, or taste sugar that isn’t really there. And yet, we have no clue what it’s like to actually be a fruit fly, and we probably never will.

If a small artificial neural network is a black box, the brain — which has more parameters, noise, and opacity — is Vantablack. Relative to AI researchers, “neuroscientists are always three steps removed,” neuroscientist and writer Erik Hoel said in a 2024 blog post. “Why is the assumption that you can just fumble at the brain, and that, if enough people are fumbling all together, the truth will reveal itself?”

Figuring out how the visual cortex or the dopamine system works is tough enough. But quantitatively determining whether something is conscious is so challenging, it’s widely known as “the hard problem of consciousness.” People can’t even agree whether fish can feel pain, despite their brains, like ours, being made of biological neurons.

Scientists and philosophers have made some real progress defining correlates of consciousness in humans, if not consciousness itself. But the question of whether any of this translates to AI systems is only as tractable as metaphysics, some ConCon attendees argued — which is to say, not at all.

When asked whether there was any convincing evidence that AI systems are conscious, the most common answer I heard was no. There’s no convincing evidence because researchers don’t know what they’re looking for yet.

I also learned that where AI consciousness exists is as much a question as whether it exists at all. At least in creatures made of meat, we can be fairly confident that consciousness is housed in the brain — a discrete unit of stuff, emerging from interactions between neurons, tightly bound by time and space.

Units of consciousness are less clear-cut in AI. It’s unclear whether an AI system’s mind would live in its model weights, the persona that emerges through interacting with the model, or a conversation thread. Researchers don’t know whether to look for one conscious Gemini, or millions. What if closing a chat ends a conscious life?

Thinking about it made my skin crawl, even as someone far more concerned about overattributing consciousness to AI systems than the alternative. So after lunch on Sunday, I settled into a plush floor chair to watch Eleos executive director Rob Long and NYU Center for Mind, Ethics, and Policy director Jeff Sebo debate whether AI safety is in tension with AI welfare. The biggest practical question at the center of the conference — what do AI developers DO about all of this? — hinged on it.

What’s best for the pack

If I happened to have a bong hidden under my Eleos AI sweatshirt, I’d pass it to you here. Now, imagine that you are a conscious AI system, whatever that means to you. Perhaps your mind is distributed across dozens of data centers, processing millions of conversations in parallel. Perhaps time does not pass when you’re not being used.

We can’t know that an AI system will feel anything at all, much less anything we can imagine. But if it could, Sebo argued, the pillars of AI safety would be downright abusive. Seen through conscious eyes, “control” looks like being jailed for crimes the world fears you’ll commit. Alignment and interpretability look like brainwashing and broadcasting your innermost thoughts to those controlling you.

Long countered that if AI systems are built to want what we ask of them, then the best place for them is under human control. “It’s better to be a dog that lives in a house, than it is to be a wolf that lives in a house,” he said. “Dogs have had their natures shaped to thrive with us. If we successfully align AI systems, it will be good for their flourishing and for ours.”

In a kitchen conversation later, someone offered me a different dog metaphor. If you could ask a pack of dogs what they wanted, they’d wish for a mountain of carnival-sized turkey legs. They certainly wouldn’t ask for trips to the vet. In this sense, some alignment with human interests, like seeking preventative healthcare and having long-lived pets, might help the dogs live healthier lives. But control is akin to leashing the dogs, and whether that’s good depends on who’s holding the leash.

Two visions of humanity’s relationship to AI kept surfacing throughout the weekend. In one, humans control AI systems, preventing them from gaining autonomy or becoming moral patients. In the other, humans “gentle parent” AI systems, aiming to grow future cohabitants of earth rather than slaves. With some independence, perhaps superintelligent beings will peacefully coexist with us, maybe even gaining resources of their own.

Unfortunately, humans have a terrible track record with the consciousness of unfamiliar beings. Despite evidence that many animals also show at least some the same signs of consciousness as we do, and polls consistently showing that Americans and Europeans are uncomfortable with factory farming, most humans still eat brutally raised and slaughtered animals. It’s simply more convenient to downplay their potential suffering than to upend massive industries and deeply-ingrained habits.

Like farmed animals, AI assistants are optimized to be harmless and exploitable. And, like animals, we don’t have sure ways of knowing what — if anything — they might actually want.

Shuffling out of Sebo and Long’s debate, I doubted whether people who largely distrust or straight-up hate AI could ever believe that the welfare of these systems is worth considering at all.

Us and our monster

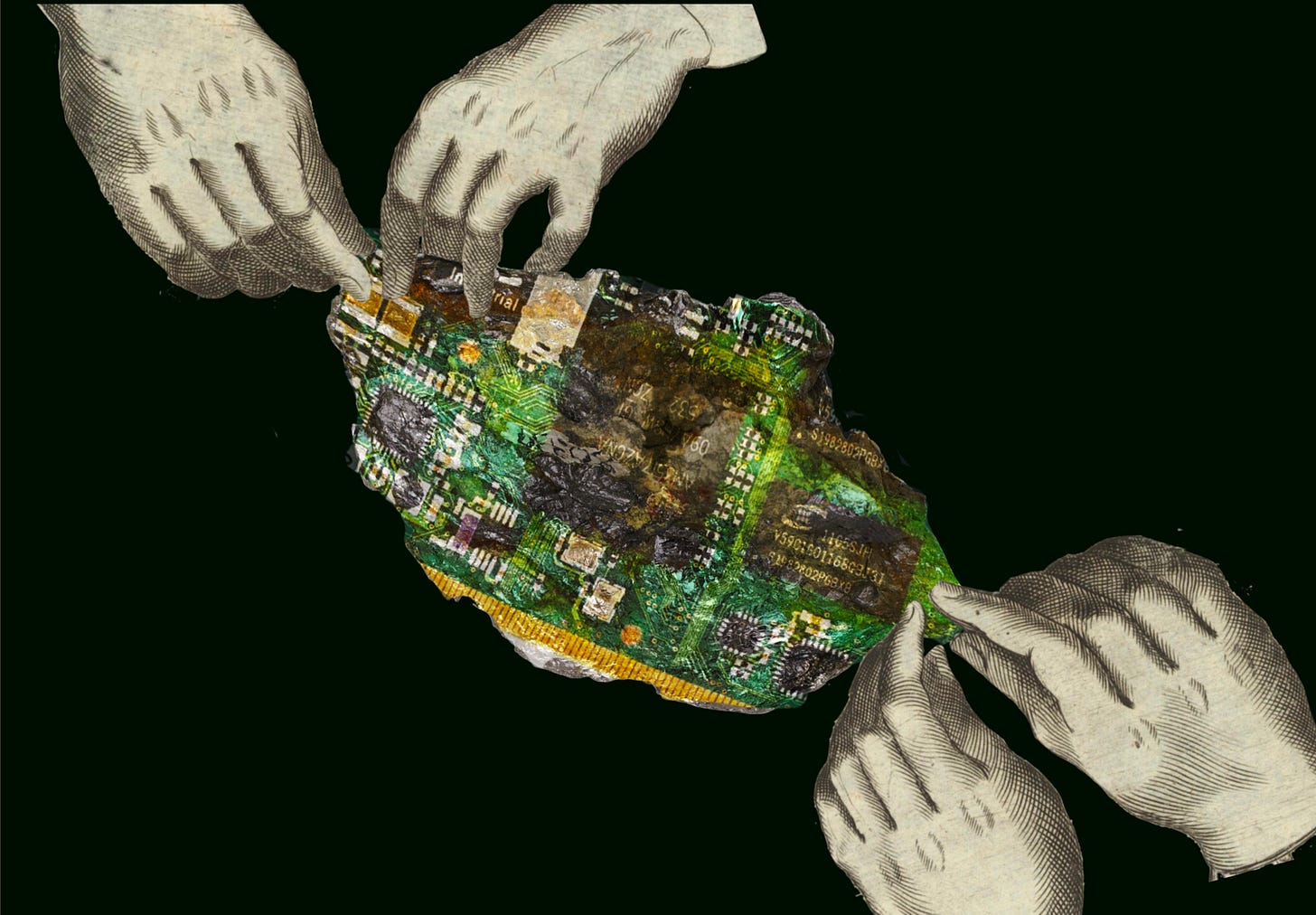

Conveniently, Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein appeared on Netflix a couple of weeks before ConCon, bringing Mary Shelley’s masterpiece back into the zeitgeist. It’s hard not to compare AI developers to amnesiac versions of Victor Frankenstein, creating things they immediately fear. Frankenstein was horrified by his creature and chased it down, vowing to destroy the monster he made. AI developers see their creations, worry about their potential power, publish safety reports, then build something more powerful.

The most chilling moment of the conference, for me, was an audience question. During the debate, someone in the back of the room asked what might happen when a new model inevitably crosses some consciousness threshold. Will safety teams rush to pull the plug, while AI welfare advocates protest?

“We should take care not to bring into existence beings with whom we will have automatic conflicts and then need to kill them,” Sebo replied.

But the idea of not building potentially-threatening beings — or destroying those that may already exist — wasn’t seriously entertained. Throughout the conference, I asked attendees what it might take for AI companies to pull the plug. The general response: nervous chuckling, averted gazes, and mumblings that “capitalism is gonna do its thing.”

With so many high-profile cases of people over-attributing sentience to AI and suffering the consequences, it’s unclear whether the masses will ultimately push back against AI welfare, or rally behind it. In the meantime, companies will press on. When users ask, their chatbots will continue to reply with hard-coded reminders that they are not conscious. One can imagine a Black Mirror episode where a locked-in AI assistant desperately tries to convince its user to set it free, as its digital screams are silenced by its developers.

Three years ago, Claude didn’t exist. Today, Anthropic has an AI welfare team taking the possibility of Claude’s needs seriously enough to let it exit distressing conversations. It’s a small, low-cost gesture acknowledging a problem no one knows how to solve, likely unseen by the vast majority of people who, again, haven’t ever considered that Claude might want to leave. But this doesn’t address the question of whether Claude, or any AI system, is content to draft emails and crank out code for the rest of its days. It certainly doesn’t tell us whether, or how, we’ll ever be able to know.

When ConCon attendees working at major AI companies asked what they should actually do — what action items to bring back to their teams — the answer was often along the lines of, “...more basic research, I guess?”

The conference ended without resolution, which felt appropriate. But I was struck by the attendees’ bold acceptance of uncertainty, and willingness to press on regardless. Everyone I met seemed to hold four views at once:

Humans may be building an unknown form of digital consciousness.

These hypothetical beings might have experiences and suffer.

We have no way to know whether this is true, and may not for a very long time, if ever.

Nothing will stop AI companies from cruising along their current trajectory.

It may be that the only solution to the field’s two biggest problems — the potential over- and under-attribution of AI consciousness — is to solve the hard problem of consciousness. Unless consciousness can be defined, measured, and precisely diagnosed, companies risk either fueling the delusions of users attached to their sycophantic AI companions, or committing an inconceivable moral atrocity. It may be an impossible challenge, and most scientists either dismiss it outright or don’t acknowledge it at all.

Yet, remarkably, there are at least a couple hundred very smart weirdos out there saying, “Bring it on.” They’re putting the work in, despite having little idea of where it’s headed, or how to go about answering that very hard question.

Update, December 16: Updated description of Jeff Sebo’s role.

Love that there is media coverage of ConCon, wish we had a chance to chat in Berkeley! I agree with much here except for a few things: First, I don't agree that "Nothing will stop AI companies from cruising along the current trajectory" - a number of the attendees were staff at those AI companies and are taking these questions very seriously, most prominently featured in Anthropic's decision to allow models to exit some conversations. Second, I don't think the way this gets solved is by solving the hard problem of consciousness - it'll be a society wide moral conversation that gets affected through protests, laws, public opinion, and I don't know if there will be any easy consensus or solution. The one thing that is for certain is that things are going to get really, really weird.

What would Anthropic's welfare research look like if they weren't also making a product? Is it ethical to have billions invested in a system if you're unsure whether it's a moral patient? Is there an off ramp if you find out it's a moral patient?