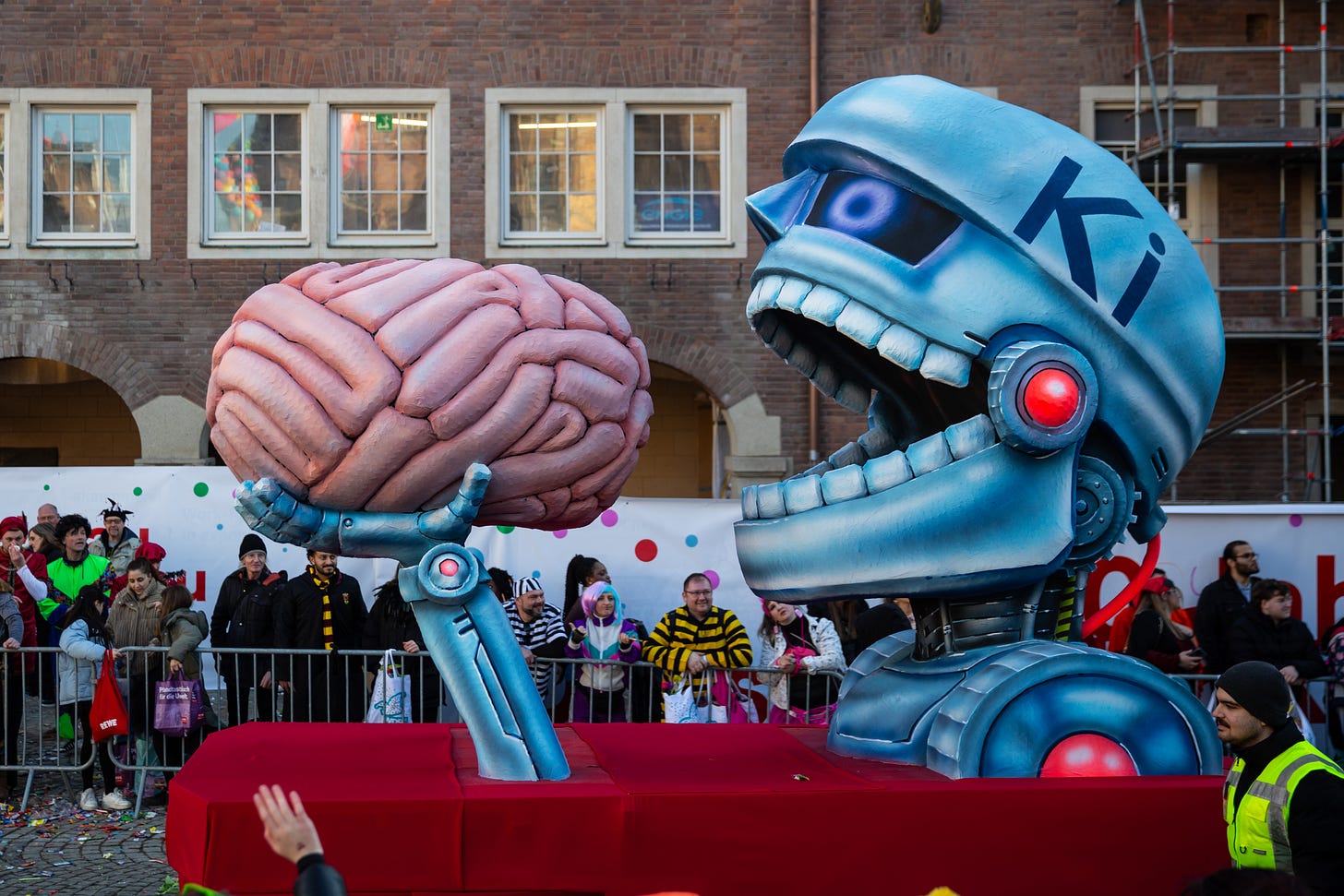

No, ChatGPT isn’t ‘making us stupid’

— but there’s still reason to worry

Over a decade before the iPhone put the internet in everyone’s pockets, philosophers Andy Clark and David Chalmers laid out their theory of the “extended mind.” We should not think of our minds as our brains alone, they proposed, but as a hybrid system that includes all of the resources and tools that help us think, “only some of which are housed in the biological brain.”

This was true when our ancestors counted with notches carved into bone, and it is still true — though on a vastly different scale — in the age of the internet and large language models. Our brains delegate a lot of work to tools and, on a purely functional level, that works very well for our minds.

“The brain’s core skill set includes launching actions that recruit all manner of environmental opportunity and support,” Clark wrote earlier this year. “The brain is unconcerned about where and how things get done. What it specializes in is learning how to use embodied action to make the most of our (now mostly human-built) worlds.” There’s no inherent downside, for example, to relying on Google Maps to get around. If turn-by-turn directions are always available and rarely make mistakes, you’ll get where you need to go whether those directions come from your hippocampus or your phone.

And yet, Clark wrote, “we humans seem strangely resistant to recognizing our own hybrid nature.” That resistance has surfaced in viral tweets and, ironically, AI-assisted LinkedIn posts lamenting that “ChatGPT users are going cognitively bankrupt.”

This is not the first time such concerns have arisen in response to a new technology. Many paradigm-shifting technological advancements, from calculators to televisions, sparked fears that overdependence on devices is making humans stupid.

Ten years ago, researchers at University College London observed that when subjects set an external reminder for a to-do list item, the part of their brains that normally reflects future plans was less active than when they had to rely on their minds alone. This is as it should be: to avoid redundancy, the brain stops storing information that can be more readily stored elsewhere.

The unique concern with ChatGPT, however, is that rather than augmenting our capacity to think critically, LLMs give us the ability to offload critical thinking altogether.

Yet hardly any data on the neurological side effects of using LLMs exists. AI has been developing at breakneck speed, and neuroscience can’t keep up. It’s not uncommon for studies tracking human brain activity to take three or more years, from conception to journal publication — longer than tools like ChatGPT have been available to the public.

That said, evidence from earlier waves of technology, including the internet, GPS navigation, and smartphones, gives us some sense of how offloading cognition affects the brain. And early research into how LLMs may be changing and accelerating these processes is starting to trickle through.

AI helps experts and hinders beginners

Back in 2011, researchers first described the “Google effect”: when people expect to have access to the internet, they usually remember how to search for information, but are less likely to remember the information itself.

Old-school googling requires following your own train of thought along a path of hyperlinks, like skimming through a pile of library books at 10x speed. When it’s reliably accessible, the internet feels like a part of us, sometimes to a fault. Dozens of studies suggest that we often mistake the internet’s knowledge for our own, artificially inflating our cognitive egos.

LLM-powered chatbots, however, present themselves as conversational partners: not an extension of you, but an oracle you consult. This dynamic — human as questioner, AI as authority — encourages a more complete surrender of cognitive agency.

Earlier this summer, an MIT study led by research scientist Nataliya Kosmyna sparked a wave of panic, and understandably so. The study, which has not yet been peer reviewed, was the first to present data suggesting that using tools like ChatGPT may change neural activity. Researchers monitored brain activity while 54 Boston-based academics wrote short essays using ChatGPT, traditional Google search, or their brains alone.

By tracking neural signals as they traveled across brain regions, the researchers spotted major differences between these groups. ChatGPT users showed the weakest neural connectivity — brainwaves corresponding to cognitive functions like concentration, memory, and creativity were weaker.

They also seemed to process information differently from people working with their brains alone. The brain-only group showed signs of bottom-up processing: brain signals mainly traveled from regions storing memories and sensory information up to the frontal cortex, where critical thinking occurs. But the frontal cortex of ChatGPT users seemed to mainly send information down to lower-level brain regions, a sign that they were filtering AI suggestions rather than synthesizing original ideas from their own mental reserves.

Moreover, when ChatGPT users were later asked to write essays unaided, memory-related brain waves seemed weaker than in users who started off writing without AI, then gained access to it later. In other words, LLM-based chatbots appear to boost performance if the user has already done the hard work of learning for themselves. But when used as a replacement for thinking, rather than a supplement, AI might prevent users from learning anything at all.

Media coverage quickly spiraled into “ChatGPT is making you dumber” headlines, prompting Kosmyna to clarify that the study did not find that AI made participants “stupid,” “dumb,” or caused “brain rot.” She emphasized that the findings were preliminary and stressed that the research showed changes in brain activity patterns during one specific task — not permanent, irreversible damage to critical thinking or intelligence.

But her research group chose the task of essay writing for a reason. Universities don’t know how to handle AI in classrooms, especially in the humanities. Studies show that using AI to draft an essay or summarize a lecture shifts the user’s role from active information-seeker to passive curator, creating an illusion of comprehensive understanding. Producing passable output without truly engaging with the source material can — and often does — lead to passing grades and decent job prospects.

This challenges the core mission of liberal arts institutions, which were originally designed as vehicles for personal growth, not utilitarian job preparation. But convincing overworked students — or anyone — to use their minds to do something that AI could do better is an increasingly tall order.

Between augmentation and automation

Recent usage data from Anthropic and OpenAI reveals distinct patterns in how people interact with different AI models. ChatGPT is increasingly being used as a personal assistant, with message volume swelling sixfold between July 2024 and July 2025. A massive new analysis of ChatGPT’s consumer product (excluding enterprise usage) found that people mostly use ChatGPT as a substitute for Google, leaning on it for general information-seeking and advice. When users do ask ChatGPT for help on writing tasks — the subject of 42% of work-related messages — it’s mostly for editing, not writing from scratch.

Claude, however, is emerging as a tool for total cognitive offloading, at least in certain corporate circles. According to Anthropic’s new analysis of roughly 1m August 2025 conversations, requests for automation — where AI produces something with minimal user input — now exceed requests for “augmentation,” where the user still does a substantial amount of their own work (49.1% to 47% respectively). Anthropic also reported enterprise API use, 77% of which involved automation requests.

Anthropic’s report suggests that the shift toward automation partially reflects an increase in user trust in the technology. But the ability to trust AI conditionally — as appropriately critical users should — may be reserved for a privileged minority of the global population. An in-depth qualitative study published in January observed that the less educated someone was, the more likely they were to blindly trust AI. Higher trust often leads to more cognitive offloading, potentially sending the user down a spiral of AI dependence.

This trend may be true on a global scale: Anthropic found that although wealthier countries have more access to Claude, they are also less likely than lower-income countries to use it for automation. This pattern suggests that access to AI tools alone doesn’t determine their impact. For those without the resources, education, and time to nourish their cognitive independence, the convenience of total cognitive offloading may come at a disproportionately high cost.

AI democratizes creativity by making us more average

In light of these usage patterns, the tech industry’s promise that generative AI will democratize creativity deserves scrutiny. Ad campaigns for tools like Google’s Veo 3 and AI music maker Suno promise to bestow creative talent upon non-artistic normies. But the handful of studies that have explored the relationship between AI use and creativity have found mixed results.

Back in 2022, a team led by computational cognitive scientist Tom Griffiths examined how professional Go players have changed their game since the advent of Google DeepMind’s AlphaGo, the first AI system to defeat a human Go champion. They found that humans started making better, previously unobserved moves after seeing AlphaGo at play. “It made me question human creativity,” one former Go champion said during a postmatch news conference. “AlphaGo made me realize that I must study Go more.”

But AI doesn’t always inspire users to go off and improve their own human craft. In the most dangerous cases, chatbots can “Yes, And” users into delusional states of “AI psychosis,” an ill-defined but increasingly concerning condition where chatbots elicit distorted beliefs in users. But the vast majority of the time, chatbots shape our thinking in much subtler ways. When an LLM provides confident, instantly-synthesized responses that tend to align with user beliefs, users get enveloped in self-reinforcing information bubbles.

Because LLMs are trained on vast datasets that reflect the statistical patterns of human language and thought, they naturally generate outputs that represent consensus viewpoints, rather than novel or unconventional perspectives. Thus, their output tends to converge toward the middle-of-the-road.

Kosmyna’s MIT study witnessed this in responses to subjective essay prompts like ”Is having too many choices a problem?”. While people who wrote essays unaided had a wide range of personal responses, ChatGPT users all wrote very similar generic essays. With LLMs, “you have no divergent opinions being generated,” Kosmyna told The New Yorker. “Average everything everywhere all at once — that’s kind of what we’re looking at here.”

When Sam Altman predicted the “gentle singularity,” he wrote: “For a long time, technical people in the startup industry have made fun of ‘the idea guys’; people who had an idea and were looking for a team to build it. It now looks to me like they are about to have their day in the sun.”

In some sense, this is true. People can vibecode apps without computer science degrees, or produce NSFW country bops without knowing how to play a musical instrument.

But an LLM is an ouroboros, digesting the internet and regurgitating its average. Researchers have found that while they can help with goal-directed tasks, like answering specific questions or copyediting documents, they hinder “divergent thinking,” or the ability to come up with novel ideas. Philosophers, educators, and psychiatrists worry about this — not necessarily whether AI is making us stupid, but whether it’s hollowing out human creativity. If art can be produced without effort, some ask, why bother?

Not rewired, but disempowered?

The field of neuroscience has hardly any evidence on whether LLMs cause long-term changes to our brains. Perhaps in several decades, with better human neuroimaging technology and postmortem studies on the brains of deceased AI users, we’ll see the anatomical damage (or lack thereof).

But the psychological and social consequences of offloading cognition to our devices are unfolding in real time. Educators don’t know how to stop students from using AI to cheat. High school seniors have the lowest reading scores since the National Center for Education Statistics started assessing them in 1992, and education experts suspect increased screen time is partially to blame. And thanks to ChatGPT, the job market for recent college graduates has become a strange hellscape: AI reviewers are sifting through a firehose of AI-generated applications, while hiring rates sink lower than they’ve been since the Great Recession.

Emerging evidence suggests that the rapid — and sometimes clumsy — corporate rollout of AI tools is threatening many workers’ sense of competence and autonomy. This is especially true for less-experienced workers, who are more likely than their senior colleagues to use LLMs instead of learning foundational skills. By outsourcing everything to AI, these employees eventually realize that they can’t function without it.

“While AI can improve efficiency, it may also reduce critical engagement, particularly in routine or lower-stakes tasks in which users simply rely on AI,” a paper by researchers at Microsoft and Carnegie Mellon University reported earlier this year. LLM users produced more homogenous outcomes than those just using their brains, reflecting “a lack of personal, contextualized, critical and reflective judgment of AI output,” which the authors “interpreted as a deterioration of critical thinking.”

More recently, Harvard researchers put over 3,500 participants through common AI-assisted work tasks like brainstorming and drafting emails, and found that working with AI “can undermine workers’ intrinsic motivation.” The authors write: “If employees consistently rely on AI for creative or cognitively challenging tasks, they risk losing the very aspects of work that drive engagement, growth, and satisfaction.”

The real question is less about becoming “stupider” as a result of AI, and more about near-term cognitive disempowerment: how AI is reshaping our relationship with thinking. Workers are losing competence and control, overstressed students are bypassing the learning process, and some people are abandoning the will to build expertise altogether. This is both an early warning sign of gradual disempowerment and a real problem unfolding now.

The closer we get to machines that can think for us, the more crucial it becomes to preserve our capacity to think for ourselves.

Something I'd like to see more examination of - when enough time has passed that we can get the data - is whether the use of AI for whole cloth creation of art eventually leads to something like burnout among its users. Part of the joy of creating art is the dopamine hit from improving over time, which isn't necessarily the case for AI art creators.

This is a good overview of the latest early evidence on how AI use is affecting us.

However, I found the framing of this piece irritating. The evidence discussed is completely compatible with a world in which offloading cognition to artificial intelligence is hindering our ability to cultivate and maintain expertise and creative thought. Such a loss of skill is within the range of what a normal person would call "making us stupid". Unless I'm missing something important?