We’re getting the argument about AI's environmental impact all wrong

Individual ChatGPT queries are a rounding error — we need to think about the future

If you mention using ChatGPT, Gemini or some other AI tool online, you can be almost sure you’ll get one type of reply: “Oh, Chat GPT wrote that email for you? That’s cool, we didn’t need that acre of rainforest anyway.”1

It’s not hard to see where this sentiment comes from. It not only draws on a message repeated day-after-day in news outlets across the world, but also clearly taps into a real and serious issue. Hundreds of billions of dollars are being invested in AI infrastructure — predominantly data centers — and these use serious amounts of energy, as well as water for cooling. Given the global challenge of climate change and local issues around stressed water resources, the question of how much energy and water AI uses is an important one.

But when it comes to our individual use of present-day AI models, the impact is much smaller than the discourse (and sarcastic replies) might suggest — and a failure to engage sensibly with the real energy and water demands of AI now risks obscuring the bigger questions about how we deal with it in the future.

A good place to start when looking at AI’s environmental impact is the data about individual queries some of the big AI companies release for their models. The latest of those suggest that one query uses 0.0002-0.0003kWh of energy and less than 0.5 milliliters of water (a tenth of a teaspoon).2 These figures are broadly comparable to the usage of a Google search around 15 years ago, before the process was further optimised. That time you asked Google how to pronounce Eyjafjallajökul, and why it meant you couldn't catch your flight, used about the same amount of energy as asking an LLM to come up with a dinner menu for tonight.

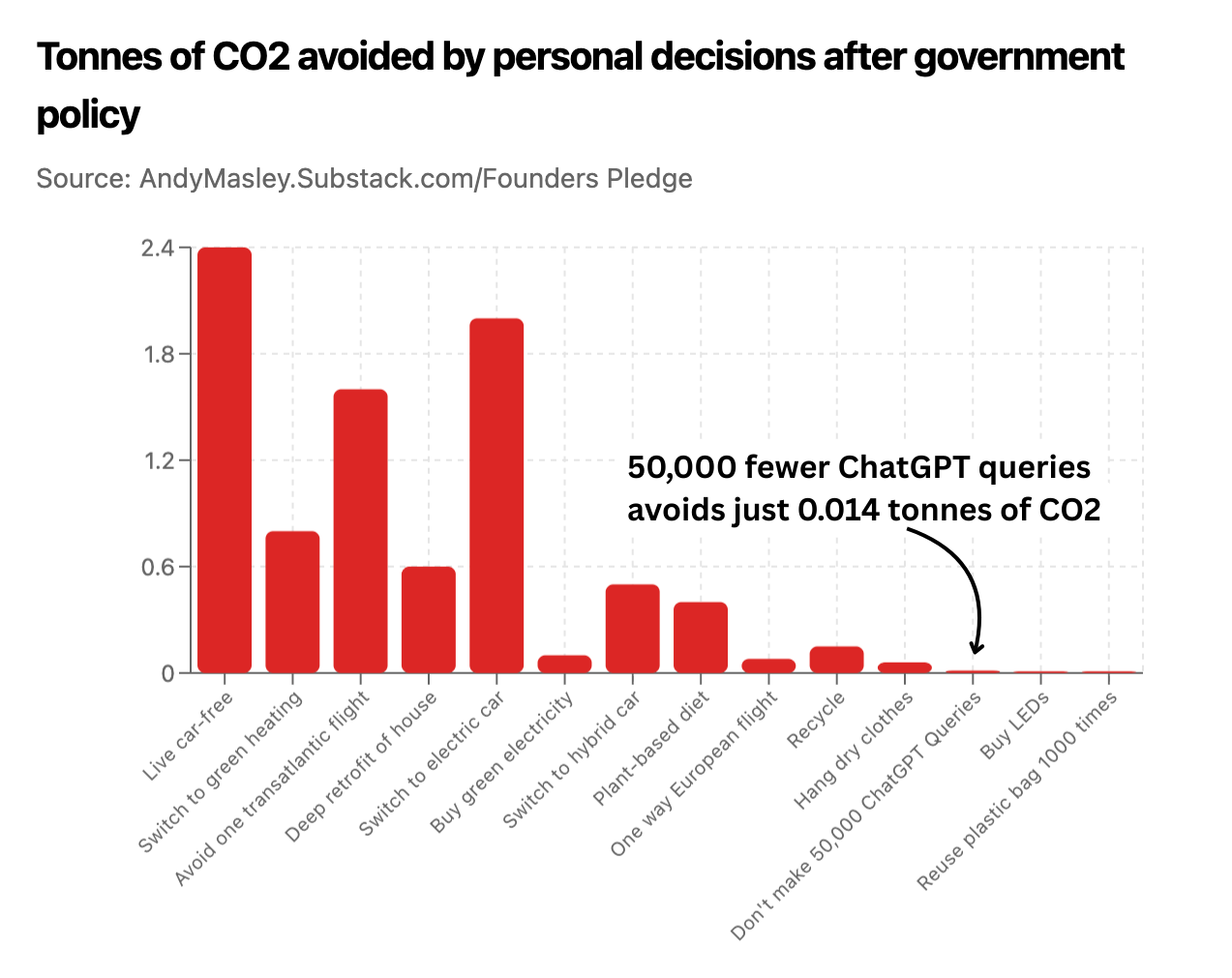

Compare and contrast that to the consumption of the average American household, which uses around 30KWh of electricity and 400 litres of water3 every day. That means a family could do 1,000 GPT queries every 24 hours and it would still amount to significantly less than 1% of its electricity or water use. A single ChatGPT query uses about the same as running a microwave for one second, or a games console for six. When it comes to our individual carbon footprint, AI is a rounding error.

The more sensible concern is the mass: every day, more of us start using AI, and infrastructure is being built on the assumption that use will increase almost exponentially. That can lead to some huge aggregate numbers. In July, the Austin Chronicle reported on the energy use of data centres in central Texas, leading to headlines such as “Texas AI centers guzzle 463m gallons, now residents are asked to cut back on showers.”

This figure is true, as is the fact that much of Texas is in drought, but the usage covers the entirety of 2023 and 2024, suggesting data centers averaged a little over 600,000 gallons a day of water use. By contrast, Texas homes use 2.3b gallons of water every single day. Even the data quoted by the Austin Chronicle suggests data centers could use a comparatively modest 0.13b gallons a day in 2025. They might use a lot of water, but data centers are a tiny contributor to overall water use.

As the Texas case shows, even technically accurate reporting can suffer from an absence of context — something which has long happened in coverage of emerging technologies. But reported figures can also just turn out to be straight up wrong. In 2019, a study claimed that watching a 30-minute show on Netflix generated the same emissions as driving for four miles — meaning streaming used more energy than driving to a Blockbuster (if they still existed) and renting the same show on DVD.

That figure was reported around the world, but it wasn’t even close to being true. A detailed debunk published by the International Energy Agency (IEA) suggested the original figure had been exaggerated by a factor of around 90. Another example comes from an infamous study from 2019 that claimed training Google’s then state-of-the-art BERT LLM produced around the same carbon as a round-trip flight from the East Coast to the West Coast. It was later found to have overestimated the output by a factor of 88, but that didn’t stop it getting cited in reputable outlets years later. The individual stories get debunked, but the narrative sticks.

To build a more informed picture of the energy and water use of AI, we need to take a step back. The rollout of AI is rapid and accelerating, so queries are increasing. New chips and data centers are more efficient than older ones, but some new models are more energy intensive. Statistics on individual queries often don’t include the energy used for training which, thanks to scaling laws, is getting ever more compute intensive. We can, however, get a starting picture of where we are at present.

“Globally, the energy consumption of data centers is a couple of percentage points – it’s about 2% of global electricity usage,” says David Mytton, a researcher on sustainable computing with the University of Oxford and the CEO of cybersecurity startup Arcjet. “Water use is significantly less. It's in the 0.1% to 0.2% range of global water usage.”

Mytton believes it is unhelpful to group energy and water together as ‘environmental’ concerns over data centers. Water use is a local issue – there is no global shortage of water, but some data centers are located in areas where local sources are already under too much pressure.

By contrast, energy use issues are both global and local: some concerns around energy center around the load on local grids, which in the West are often already overloaded4 and unused to dealing with increasing demand, but broader concerns on energy use are grounded in climate change and AI’s contribution to global warming. Issues around AI’s water use could be solved almost entirely by taking more account of it when choosing sites. Energy is a more complex problem.

Bad coverage of AI energy use takes the amount consumed by a query today, the projected growth rate of AI use, and multiplies them together to get a huge figure — something Mytton is keen to warn against.

If the number of AI users doubles (or existing users make twice as many queries), it is tempting to say the environmental impacts will double. But as models shift from development to production, huge work is done to improve their efficiency, just as the typical energy use of streaming dropped dramatically as it rolled out, or Google searches before it. With AI, there are also other models for compute being considered – Mytton points to Apple’s approach of running its AI on your device5, rather than its data centers, as an example of this.

Predicting the increased energy demand from AI data centers might be a challenging task, but there are some credible attempts at doing it. Analysis by data scientist Hannah Ritchie of an IEA report suggests the projected global increase in electricity demand from AI by 2030 is likely to be 223 terawatt-hours (equivalent to the annual electricity use of South Africa).6 Air conditioning is expected to drive around three times as much usage, at 697 TWh, and electric vehicles even more at 854 TWh. All of these are dwarfed by anticipated growth in building and industrial uses.

Of course, the more optimistic you are about the development of AI in the next five years, the more dramatic your energy forecasts are likely to be. The IEA expects AI to be a major driver of increased electricity demand, but its scenarios fall short of technology resembling artificial general intelligence (AGI).

Such a model will likely require huge amounts of training compute, will be compute intensive to run, and see very high demand. Both research and deployment energy use, then, would increase significantly. The research institute Epoch AI has forecast a range of scenarios for future energy use that exceed those of the IEA. The researchers make different estimates based on forecast chip demand, recent power growth in AI data centers, and estimates from EPRI on data center growth.

These result in estimates of global data center energy use between 50% and 100% higher than those of the IEA by 2030 — suggesting AI would be a major factor in increasing global energy demand. One truly jaw-dropping stat from the Epoch AI research suggests that by 2030 the most advanced AI training run alone could use 1% of the electricity used by the USA today. Yet even in this high-use scenario, AI energy demand growth is still only on a par with aircon or electric vehicles.

Of course, the questions of the actual environmental damage caused by AI data centers will depend greatly upon where and how they are built. One built somewhere with abundant water supply and clean energy generation will cause almost no damage. One reliant on fossil fuels and scarce water, such as xAI’s methane-powered facility in Memphis, will cause damage both locally and globally.

The optimistic case for green AI growth looks something like this: AI data centers are major (though not exceptional) energy and water users, but their growth can be mitigated through considerate locating of sites, clean energy use, and efficiency improvements.

That optimistic case, however, is difficult to square with some recent remarks from senior executives. At a Washington DC AI conference, interior secretary Doug Burgum attacked “climate extremist” agendas and pledged to use “incredibly clean” coal, gas and other fossil fuels to expand America’s energy grid for AI. Alphabet and Google’s chief investment officer praised the remarks as “fantastic… to realize the potential of AI, you have to have the power to deliver it.”

One rationale for using fossil fuels to power American data centers is the idea that China is doing the same — and on energy infrastructure, China has a head start on the US. Western grids have been managing static demand for decades, while China’s grid has expanded to keep pace with its economic growth, meaning in multiple regions of China, data centers have access to virtually free surplus energy.

However, David Fishman, principal at energy consultancy The Lantau Group, says the idea that Chinese data centers are powered by dirty energy is a misnomer. “Data centers explicitly have to be green, or most of them do,” he says. “Eight national computing hubs account for something like 70%-ish of all the compute power in China, and they have to be 80% renewable.”

China’s AI race is in a useful symbiotic relationship with its energy industry, he adds. China has built so much wind and solar in so little time that it has too much — so to avoid “curtailment,” wind and solar projects have to demonstrate they have an end user in place, or else they will be paused until grid infrastructure catches up. Data centers provide just that demand, even well away from population centers.

That green energy abundance problem is not one the US is likely to face in the near future — but it does suggest that neither electricity nor water use need be limiting factors to AI rollout, if they are done responsibly.

The question remains whether US or European nations can manage the planning challenges of that rollout, especially amid a tech and AI backlash. AI uses energy, but not nearly so much as heating, eating or getting around. The public are convinced we need the latter three. Can they be convinced AI is similarly essential?

This is a real post, but I’m not linking it so as not to pick on one particular user.

These recent reports have been helpfully collated by Ethan Mollick of the Wharton School, but they are already attracting some controversy – one critique is that the water use estimate is understated because it doesn’t include the water used to generate the power. However, that analysis notes the eventual water use is still relatively low.

This only includes direct water use of households – it doesn’t include water used to generate the electricity the household uses, for example. Water use statistics of data centers are often criticised on similar grounds, though you can end up double- or triple-counting the same water use if you carry it up the supply chain.

This is true both in Europe and across the USA and causes trouble for suppliers and would-be energy users alike – new capacity is sitting unused waiting for connection, and data centers and other users are looking to off-grid generation rather than wait for grids to catch up. In some cases, they are allegedly resorting to polluting on-site fuel generation to power data centers.

At present for a small subset of queries, but Mytton believes the intention is to run an increasing share of queries locally.

There is a big range between their “low demand” and “high demand” scenarios, ranging from 118 TWh to 383 TWh. Given the acceleration of the AI race, the higher estimates might feel most plausible, but even those estimate that data centers would remain a tiny part of overall electricity usage.

Since I keep hearing stories about AI hallucinating and one of the keenest advocates for AI is Elon Musk perhaps we should reconsider?

🔥