The perils of AI safety’s insularity

By building their own intellectual ecosystem, researchers worried about existential AI risk shed academia's baggage — and, perhaps, some of its strengths

The foundations of modern AI were laid in academia. Before the field of machine learning had a name, neuroscientists, psychologists and theoreticians introduced the first artificial neural networks. Many of the basic processes that help AI learn, including backpropagation and reinforcement learning, were also formalized within university walls.

In theory, a university lab could have made the technical breakthrough that led to GPT. Less than a decade ago, training a language model only required a handful of GPUs — well within an academic’s means.

Instead, those breakthroughs were made by OpenAI in 2018, following Google’s introduction of the transformer the year before. Today, it’s taken for granted that state of the art AI models are built in private spaces, shielded from the institutions that originally made them possible.

The same is true of AI safety research. Rather than being done in academia, the work of making AI models safe and secure is increasingly performed by AI companies themselves, or at non-profits that are better resourced, and can move faster, than universities.

This shift may have been inevitable. Capitalism is a powerful force, and AI’s commercial potential demanded more resources than the ivory tower could provide. But as with so many things in AI, the inevitable is not necessarily good.

The woes of academia

Modern AI alignment, a field devoted to making artificial intelligence act in accordance with human values, grew from work by Eliezer Yudkowsky, who founded the Machine Intelligence Research Institute (MIRI) 25 years ago. His writings on existential risks like recursive self-improvement — and his lengthy fan fiction, Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality — are credited by many of today’s most prominent researchers as formative to their decision to join the field.

In the decade or so following MIRI’s launch, a handful of established academics brought conversations about alignment to mainstream ML researchers. Oxford University professor Nick Bostrom popularized the paperclip maximizer thought experiment in a 2003 philosophy paper, and 13 years later, computer scientist Stuart Russell founded UC Berkeley’s Center for Human-Compatible Artificial Intelligence (CHAI).

But until quite recently, most academics wrote off alignment — and the community of AI researchers focused on existential risks, more broadly — as “very fringe,” says David Krueger, an AI professor at the University of Montreal. Or as Naomi Saphra, an interpretability researcher at the Kempner Institute at Harvard University and incoming professor at Boston University, put it: “It’s the kind of suspicion you have about someone who’s trying to recruit you to their religion.”

As the idea of transformative AI becomes more mainstream, safety research is gaining traction within traditional computer science departments. It’s a “super, super hot topic,” Saphra says. “Academia is not hurting for students.” The ML Alignment & Theory Scholars (MATS) program, a training program that connects early-career researchers with mentors, has seen a roughly 20x increase in applications over the past three years. Today, its admission rate is nearly as competitive as Harvard’s.

Yet academia inevitably struggles to keep up with the resources directed at AI development by private money. Training a frontier model in 2025 requires north of 100,000 GPUs, hundreds of millions of dollars in compute, and a dedicated team of expensive engineers. “Computer science in academia is not structured to support that,” says FAR.AI founder Adam Gleave.

It’s not structured to support the breakneck pace of AI, either. In sciences like biology or astrophysics, getting results worth publishing can take an entire six-year PhD program, if not longer. But in AI, experiments are snappy, competition is fierce, and top language models are closed to anyone other than their developers. “Many researchers feel like if you want to work on state-of-the-art models, you have to work in industry,” Krueger says. In reality, access varies within companies, with some employees reporting having little more than academics. But the perception persists. For some, he says, “It feels like the work you’re doing is less relevant if you don’t have model access.”

The field is moving so quickly that traditional peer-reviewed publications can’t keep up. Even the stodgiest old heads in machine learning have largely ditched established journals for preprint servers, where they can dodge sluggish, dysfunctional publishers and minimize their odds of getting scooped. Writing papers still takes time, though — a huge turnoff for AI safety researchers with shrinking timelines to human-level AI. As Jacob Hilton, an ex-OpenAI researcher who now runs the Alignment Research Center, says, “Someone who thinks AGI is going to take off in the next two years might think, ‘We need to be kicking into action. We can’t be standing around writing.’”

So the AI safety community built its own parallel universe for knowledge creation. Here, eager young researchers can get trained, find funding, and self-publish in step with the latest model releases — all without leaving the field’s ideological island.

In many ways, it represents a radical experiment in scientific organization, shaking loose the institutional baggage of traditional ML research. But in doing so, AI safety researchers may be solving academia’s problems by creating their own.

Inside the frontier

In the early 2010s, people aiming to build highly intelligent AI systems for humanity’s benefit found homes at organizations such as DeepMind, which granted them the freedom to pursue topics like AI alignment and interpretability with more resources, dedicated research time, and prestige than universities could offer. Now, the most important components of cutting-edge LLMs are predominantly developed within the tech industry.

Before commercial tools like ChatGPT broke into the zeitgeist, companies like DeepMind and OpenAI were relatively welcoming of basic research. Hilton, who studied RL at OpenAI between 2018-2023, told Transformer, “I was relatively well-insulated. Even as the commercial organization was spinning up, there was still space for people who wanted to pursue research that didn’t necessarily have a commercial application.” But, he added, “trying to remain insulated from commercialization now is probably somewhat different.”

While many call for-profit AI companies “labs,” they’re not labs in the purest sense — they’re businesses with profit motives and deep ties to the wealthiest corporations on the planet. Starting around 2022, as companies like DeepMind and OpenAI began commercializing their products and accelerated their race toward superintelligence, they clamped down on what staff could publish and post online. Even the most rigorous, well-intentioned researchers can get thwarted by a comms team wary of publications that could spook the public or give the competition a leg up.

One former employee, who requested anonymity due to concerns about professional retaliation, remembers OpenAI’s review process as an “enormous apparatus” of policy, communications, and legal staffers combing through papers and blog posts for potentially unflattering implications. Most feedback from outside the research team addressed optics rather than rigor or merit. “It definitely shapes what projects people are even willing to take on,” he says. “If you anticipate that you won’t be able to get cleared to publish something, you wonder, ‘Why would I pour all this time into it?’”

One might assume that a frontier company would want to lead with optimism about the world AGI will create, to convince potential regulators and consumers that they’re not doing anything wrong. When internal research revealed that smoking cigarettes dramatically increases lung cancer risk, for example, the tobacco industry embraced a fairly straightforward brand of gaslighting: blow smoke and cloud the public narrative.

AI developers rely on a more imaginative form of corporate misdirection: safety-washing. Rather than deny the risks outright, company leaders warn that the powerful models they’re rushing to build could have “catastrophic” consequences and bring “grievous harm to the world.” Then, they reassure the public by saying that they, the Good Guys(™), are doing safety research to build the benevolent version of the potentially dangerous thing. In fact, they must build it as quickly as possible, before the Bad Guys build it first. The benefits of transformative AI, they argue, will be worth it. Rather than hiding or denying the risks, like the tobacco industry of yore, AI companies weaponize them.

So, researchers yearning to study AI safety without the corporate constraints of industry or the institutional baggage of academia often choose a third path.

An ecosystem of non-profits

What academic labs lack in compute and compensation (the average computer science PhD stipend is roughly a fifth of OpenAI’s median technical staff salary), they make up for in intellectual autonomy. Non-profits like Apollo Research and Redwood Research aim to do fast-paced AI safety research outside industry’s profit-driven constraints, while giving teams the kind of freedom they’d experience in academia. But federal funding agencies have a limited appetite for alignment research, so most organizations working in and around AI safety turn to donors motivated by the risks posed by transformative AI.

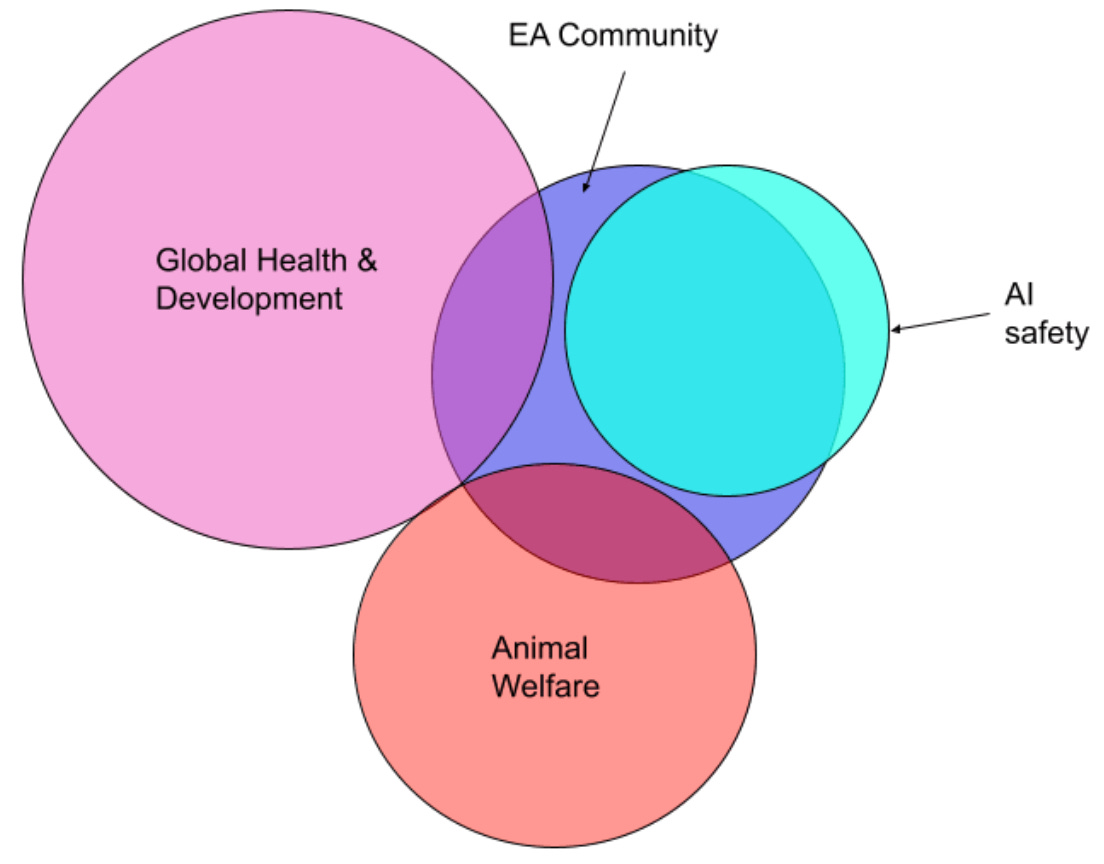

These funders very often have strong ties to effective altruism, a philanthropic movement that aims to maximize do-gooding by prioritizing tractable causes with large impact. What began as a small community largely focused on malaria bednets, deworming programs, and donating kidneys now steers tens of billions in grants and lists existential risks from AI among its top concerns. And while the effective altruism community makes up just a small part of global health or animal welfare work, it dominates the AI safety ecosystem (in part because effective altruism was so early to prioritize solving AI-related risks).

Perhaps the most high-profile funder associated with the world of effective altruism is Open Philanthropy, which recently rebranded as Coefficient Giving (and is also the primary funder of Transformer). Since January 2024, Coefficient Giving alone has put more than $205m toward groups “navigating transformative AI,” including non-profits, universities, and individual researchers.

A sizable amount of academic and field-building programs that train alignment researchers, like MATS and ARENA, are also funded by a tight circle of EA-aligned donors. Or take METR: a non-profit explicitly formed to run evaluations of frontier AI models. METR’s founder and several researchers come from frontier labs, and it hired alums of EA-affiliated funding and recruiting orgs such as Coefficient, Longview Philanthropy, and 80,000 Hours. METR was originally a project of the Alignment Research Center, whose founder, Paul Christiano, used to work at OpenAI and is now the head of safety at the US Center for AI Standards and Innovation — and happens to be married to a senior AI advisor at Coefficient Giving.

Funding ties and collaborative projects aren’t the only connections binding the field together. One would be hard-pressed to find a Bay Area-based AI safety researcher who did not have a handful of close friends, coworkers, and lovers working in their office or in a frontier lab.

These connections enable the level of close collaboration and information-sharing the field demands, and given the relatively small talent pool that exists in AI safety, which labored almost alone for close to a decade, a tight social network isn’t surprising. But there is always an inherent tension between the companies building AI and the people trying to ensure they do so safely. Even when these tensions are navigated in good faith — which, according to sources I spoke to, generally seems to be the case — it at the very least creates the appearance of conflicts of interest.

Again, this isn’t unique to AI safety. Academics mostly dating each other is so common that the “two-body problem” — couples struggling to find faculty jobs at the same institution — has a name. But when funders and researchers live and work in the same handful of buildings scattered across a small handful of cities — two of which, Berkeley and San Francisco, are just 13 miles apart — it creates an intellectual bubble where groupthink may be mistaken for truth, and where a select few ideas can come to dominate the field’s priorities.

Take the recent surge of interest in mechanistic interpretability, which Center for AI Safety director Dan Hendrycks has called “misguided” and attributed to “the sentiments of Anthropic leadership and associated grantmakers.” Researchers in the natural language processing (NLP) community have also expressed frustration with the recent influx of eager mechanistic interpretability trainees — specifically, that they “don’t meaningfully engage” with mainstream academic venues, and therefore have a tendency to “reinvent” or “rediscover” existing methods.

The demand for advisors has nevertheless pushed some academic NLP researchers to embrace mechanistic interpretability, Saphra and coauthor Sarah Wiegreffe wrote in a 2024 paper. “Who wouldn’t want to work on mechanistic interpretability? Students need advisors. Funders need grant recipients. There is free pizza.”

(This week, Google DeepMind announced that it was effectively pulling back from some of its mechanistic interpretability work.)

In a paper published earlier this year, a team of researchers expressed concern that the study of “scheming” behaviors in AI systems risks repeating failures that ape language researchers made 50 years ago. They present a cautionary tale of how confirmation bias and insularity can undermine even the most well-intentioned research agenda:

“Most AI safety researchers are motivated by genuine concern about the impact of powerful AI on society. Humans often show confirmation biases or motivated reasoning, and so concerned researchers may be naturally prone to over-interpret in favour of ‘rogue’ AI behaviours. The papers making these claims are mostly (but not exclusively) written by a small set of overlapping authors who are all part of a tight-knit community who have argued that artificial general intelligence (AGI) and artificial superintelligence (ASI) are a near-term possibility. Thus, there is an ever-present risk of researcher bias and ‘groupthink’ when discussing the issue.”

The authors aren’t arguing that risks like scheming shouldn’t be taken seriously — quite the opposite. “It’s because the authors take these risks seriously that they think experts should be more rigorous and careful about their claims,” reporter Sigal Samuel wrote for Vox.

Silo-building, gatekeeping, and tribalism are common side effects of expertise in any field. But AI safety is especially walled off, intentionally so. The field’s high geographic concentration in London and the Bay Area blurs personal and professional relationships; especially in EA and rationalist circles, researchers sometimes exclusively live with, date, and hang out online with each other. By closing themselves off to collaborators outside their small community, both subconsciously and systematically, earnest researchers risk getting lost in their own epistemic universe.

The problems of peer review

Insularity can, of course, be very efficient. “If you know someone, and you can just message them, and they know you, it’s just so much easier,” said Alex Altair, an independent researcher who recently vetted applicants to his new team, Dovetail. “When a random person applies,” he told me, “I’m like, ‘Well, now I have to vet you.’ They’re literally a random person from the internet…if it’s someone I already know, it’s just so much easier.”

Efficiency matters in AI, where things move very quickly and many believe that superintelligent AI will dramatically disrupt or destroy humanity within the next decade, if not sooner. “If you publish at a conference, even the fastest ones take like, three months,” said Marius Hobbhahn, CEO of Apollo Research. “Three months at the frontier is like three years in the rest of the world.”

Beyond being slow, the traditional academic process of peer review, designed to ensure research can be tested by a wider community, can be exceptionally bad in computer science. Reviewing dense technical papers is obligatory, hard, and unpaid: a trifecta that increasingly convinces overworked academics to offload peer review to ChatGPT. It’s such a problem in the field that ICML, a major machine learning conference, recently added an extended statement to their “Publication Ethics” page condemning the practice. (It also banned authors from fighting back with hidden prompts “intended to obtain a favorable review from an LLM.”)

So, ML researchers of all stripes publish papers on arXiv, a preprint repository where work can be shared before completing traditional peer review. That, in turn, reduces the need for publishing in journals or at conferences. “Machine learning moves so quickly [that] the big papers at a conference, people have usually already seen on Twitter,” FAR.AI’s Gleave told Transformer. There’s less incentive to publish at NeurIPS or ICML if your impact and intellectual clout mostly depend on “how many Twitter likes you get.”

Some also publish their findings primarily (or at least initially) on LessWrong, a popular rationalist community forum that has become a de facto gathering place for many alignment researchers. LessWrong, and its more-selective offshoot the AI Alignment Forum, both host detailed, good-faith, quick-turnaround discussions that are rarely seen in traditional venues.

But LessWrong also hosts blog posts about transhumanism, techno-eugenics, and itself, and has historically endorsed a number of unsubstantiated claims, like “AIs will be ‘rational agents” and “AIs might make decisions based on what other imagined AIs might do.” These claims, Krueger wrote on the forum, lead some more-established academic researchers to conclude “that people on LW are at the peak of ‘mount stupid’” — the high-confidence, know-nothing heights of the Dunning-Kruger effect. To get Alignment Forum membership, authors must first gain “significant trust” from existing members, which the site says one may earn by “produc[ing] lots of great AI alignment content, and post[ing] it to LessWrong.” Working on AI alignment professionally, moderators say, is not sufficient.

In a 2023 LessWrong post, Krueger wrote about how, when asked, non-academic AI safety researchers tend to list three reasons why they don’t publish in traditional ML venues:

(1) “All the people I want to talk to are already working with me.”

(2) “We don’t know how to write ML papers.”

(3) “We are all too busy with other things and nobody wants to.”

The need for change

By prioritizing speed and familiarity, a small, homogeneous community is currently driving much of society’s preparation for transformative AI. That means ideas are not getting the scrutiny they deserve. It means research coalesces around a few small clusters, rather than spreading bets widely. And it means that, at least in some circles, there is considerable distrust of the AI safety ecosystem’s work.

The systems that bog down other fields of Western science — peer review; credentialing; years of training — also earn scientists a great deal of public trust. The vast majority of American adults are confident that scientists will act in the best interests of the public, according to a survey conducted last year by the Pew Research Center.

AI safety researchers, meanwhile, may or may not identify as scientists, or as technical thinkers at all. By creating their own intellectual ecosystem, they shed the slow, anachronistic processes that clash with the speed and scale of powerful AI. At the same time, the field gave up its guardrails and the inherited legitimacy of academia.

At frontier labs, the same insularity blends with commercial pressure, creating incentives to be selective about what research does and does not get published. And without formal vetting systems or real incentives to pass work along to unfamiliar reviewers, labs are free to apply different standards to different papers depending on their conclusions. At OpenAI, a former researcher told Transformer that “there’s a much, much lower bar to make claims about how good AI is going to be than to talk about the downsides.”

It’s bad that AI companies are checking their own homework, but it does help research move quickly. This work is often shared without paywalls and sparks vigorous discussions (if only in select circles) — certainly features, not bugs. It’s hard to square that circle.

But if the stakes of transformative AI are as high as the AI safety community says they are, that circle does need to be squared. Expertise is important and speed helps, but neither will matter unless the field can engage with, and earn the trust of, the world beyond its bubble. AI safety’s insularity may otherwise become a liability.

Thanks for writing and highlighting the issues.

1. Do you have concrete recommendations?

Some counterpoints:

2. Big one is UK aisi has made big push to get traditional academics involved, eg with a conference in November, or, £15m grant where they could only fund half the projects they wanted to fund.

3. Book "if anybody builds it everyone dies" was intended for public, with huge effort to reach many ppl.

4. Most MATS scholars publish into a main conference. The ones who don't publish is because the research they do is not interesting for academics, eg the work done by Palisade.

5. MATS is silver sponsor at neurips.

6. There has been close collaboration between ai2027 ppl and AI as normal technology ppl, the two most viral "big picture" perspectives on AI this year

7. There is tarbell fellowship to help upskill ppl in journalism.

8. I don't think your critiques apply to AI governance research? Or at least to a much lesser degree.

I feel like I could keep going actually... I'd be interested to know what you think! I think the article could have been more nuanced and balanced

I have read plenty of critical pieces and blog posts on EA, AI safety, rationalism, and long-termism. I think this may be at the top for me, because you've done something that other critics (Gebru, Torres, Bender) often fail to do: distinguishing individual motivations from movement-incentivized motivations and corporate-incentivized motivations.

As you say, from the perspective of someone who simply wants to do research that benefits humanity, there are only a few options.

If you don't have the money to self-fund your research so that you can have true independence from a corporation, an academic institution, or funders' preferences, then you are unfortunately stuck in the drought of aligning your vision with one that will appeal to someone willing to fund your life. And sure, sometimes, or oftentimes, people happen to find a group of like-minded individuals doing similar things. But even then, if we look at a small org, often behind that org there is a bigger fiscal sponsor or funder deeply embedded into either a research agenda led by a larger organization or funding institution, or a corporation.

So what must researchers do? Talented people who don't want their judgments constrained by financial motivations.

So far, my experience has been that you must resist the temptation to lock yourself into one revenue stream or one source of income or funds for your life, for your research. I know it takes more toll and time and cuts your slack, but having multiple income or revenue streams may be the only way to go if you want to remain truly independent in thought and will. For example, you may choose to have paid work that has nothing to do with your research and also apply for grants if you can find any grantor willing to give you a small amount of money. You may also want to have an ample network both in academia, in the corporate world, and in less strongly aligned circles.

I think that having a network of people across all domains and knowing exactly which stakeholders you wish to inform with your research may be the cure against insularity.

And it's something that keeps you humble and honest, because once you see if your research actually helps in the ways you envisioned, then you should be better calibrated to either keep going or focus your efforts elsewhere. If you are constantly being fed the idea that your research matters, but the rest of the people still don't care, or it doesn't matter whether other people care as long as one specific law gets passed or one practice in a big lab changes, then maybe that also endangers your own capacity to stay objective as to whether your research is actually impactful or not.

Traditional theories of impact are also built, in my experience, to appeal to a specific mindset. For example, following the logic of a specific funder that wants X number of people to convert to working full-time in AI safety or X number of practices to change in specific groups in specific companies.

As a lawyer, I've always hated the tendency of the law to regulate and let implementation be figured out later. I'm afraid that people in the AI safety community may be doing the same when they focus years of their life on research and then hope that the policy and legislative aspects of it, or governance aspects, are simply picked up by other people. Like, this is my part of the problem to deal with. As for the rest, somebody else can think about it. Can you at least think of who that somebody else is? Who is that somebody else to begin with? Can you aim at making your research available to the type of person that you think needs to pick up where you left off?

Those are the additions I would make to this piece. As for the rest, congratulations to Celia for writing it in a way that is fair, not to a movement, not to an ideal, but to individuals who actually care.