Japan’s unusual approach to AI policy

The country’s penalty-free AI legislation relies on social pressure and voluntary compliance — and experts say it could work elsewhere

Last month, comprehensive AI legislation came into full force across Japan. Yet the sweeping new rules contain an omission some might find striking: no punishment for non-compliance.

Japan has set itself apart from both the EU’s penalty-heavy rulemaking and the US’s mostly hands-off market stance. Experts say its strategy could provide a blueprint for smaller nations grappling with how to govern AI without stifling innovation.

“Japan’s ‘third way’ approach is not a compromise. It’s more of an architecture. It builds a framework that accelerates innovation because it addresses safety concerns, not despite them,” says Joël Naoki Christoph, an independent analyst on Japan’s AI and tech policy.

The Japanese context: why punishment does not work

Japan’s regulatory philosophy stems from a mix of economic and cultural factors. The nation is facing severe labor shortages due to an aging population, leaving it with an expected shortfall of almost 800,000 IT professionals by 2030. Policymakers want to coax risk-averse Japanese companies to adopt AI without scaring them, as it is seen as crucial to solving the nation’s productivity and labor problems without bringing up the hot-button immigration issue.

Last week, OpenAI released a paper saying that AI could “write the next chapter of Japan’s economic story,” citing economic forecasts that suggest AI could unlock over ¥100t ($650b) in economic value. For comparison, Japan’s nominal gross domestic product was ¥616t in the 12 months ending March 2025.

“In Japan, we have a culture where it’s shameful to make mistakes. Japanese companies would not try to innovate if we had hard laws from the beginning,” says Kyoko Yoshinaga, project associate professor at Keio University Graduate School of Media and Governance, who helped draft AI business guidelines with Japan’s economy ministry.

“When the government says, ‘Do this,’ companies often obey rules, even if they’re not legally binding. In Japan, there’s a culture of following directives from authorities, and usually, major organizations are invited in the rulemaking process.”

A Japanese government survey released earlier this year found that only 23.7% of Japanese companies planned to proactively use AI, versus 39.2% in the US and 48.5% in China.

Japan’s AI Promotion Act, which was passed by the Diet in May, creates a duty for organizations to cooperate with authorities. Meanwhile, the government can gather information about rights or safety infringements and provide practical guidelines for businesses. These guidelines can be flexibly updated as technology evolves. The most recent AI Guidelines for Business, published by two government ministries, provide values such as human dignity that businesses should respect, and guiding principles, such as consideration of bias.

Nevertheless, the government still has ways to police harmful AI use under existing hard laws. For example, defamation law could be applied to someone’s likeness being used to create a deepfake. Social sanction will also play a big role in mitigating risk, experts say, as misuse of technology can be extremely damaging to a company’s reputation if it comes to light. For example, when a student created an AI application claiming to identify autism from photos, public backlash forced its removal last year.

Crucially, Japan’s approach is built to evolve. “Depending on the future levels of adoption and cooperation, Japan may keep the level as is, or decide to introduce sanctions and penalties,” says Merve Hickok, an AI ethicist who is president of the Center for AI and Digital Policy.

Yoshinaga says that the development of artificial general intelligence — much more sophisticated systems than currently exist — would also require tougher regulation.

Global blueprint

While Japan’s approach reflects specific domestic concerns, experts and policymakers say it could provide a blueprint for countries elsewhere.

“This approach can scale up in countries where societal needs are prioritized and safety is an important element of the culture,” says Hickok. “Japan understands that social acceptance is critical for wide and deep adoption of this technology and that trust needs to be built and nourished.”

Other countries where trust in government is high and the private sector can be counted on to cooperate, such as Singapore, are taking similarly soft legal approaches to AI. But beyond high-trust societies, Keio’s Yoshinaga says those with emerging AI ecosystems that lack the “institutional capacity or resources to implement comprehensive, binding AI regulation” could look to Japan.

“In such cases, soft law can serve as a practical starting point, helping to build norms and trust without stifling innovation,” while keeping costs low for companies and being easy for policymakers to update.

A flexible, pragmatic approach also suits countries that, like Japan, see their future as AI consumers rather than creators of foundational models.

“Building on top of global platforms seems inevitable,” says Kenji Kushida, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Asia Program. “Becoming good users is important.”

This may give Japan unexpected leverage over global AI players. The social sanctions that shape domestic companies’ behavior could extend to international firms operating in the Japanese market and creating a form of soft regulatory export, where cultural expectations influence global companies’ behavior. If OpenAI intends to take advantage of the economic opportunity it says exists in Japan, it will need to play by the country’s rules.

Political turmoil

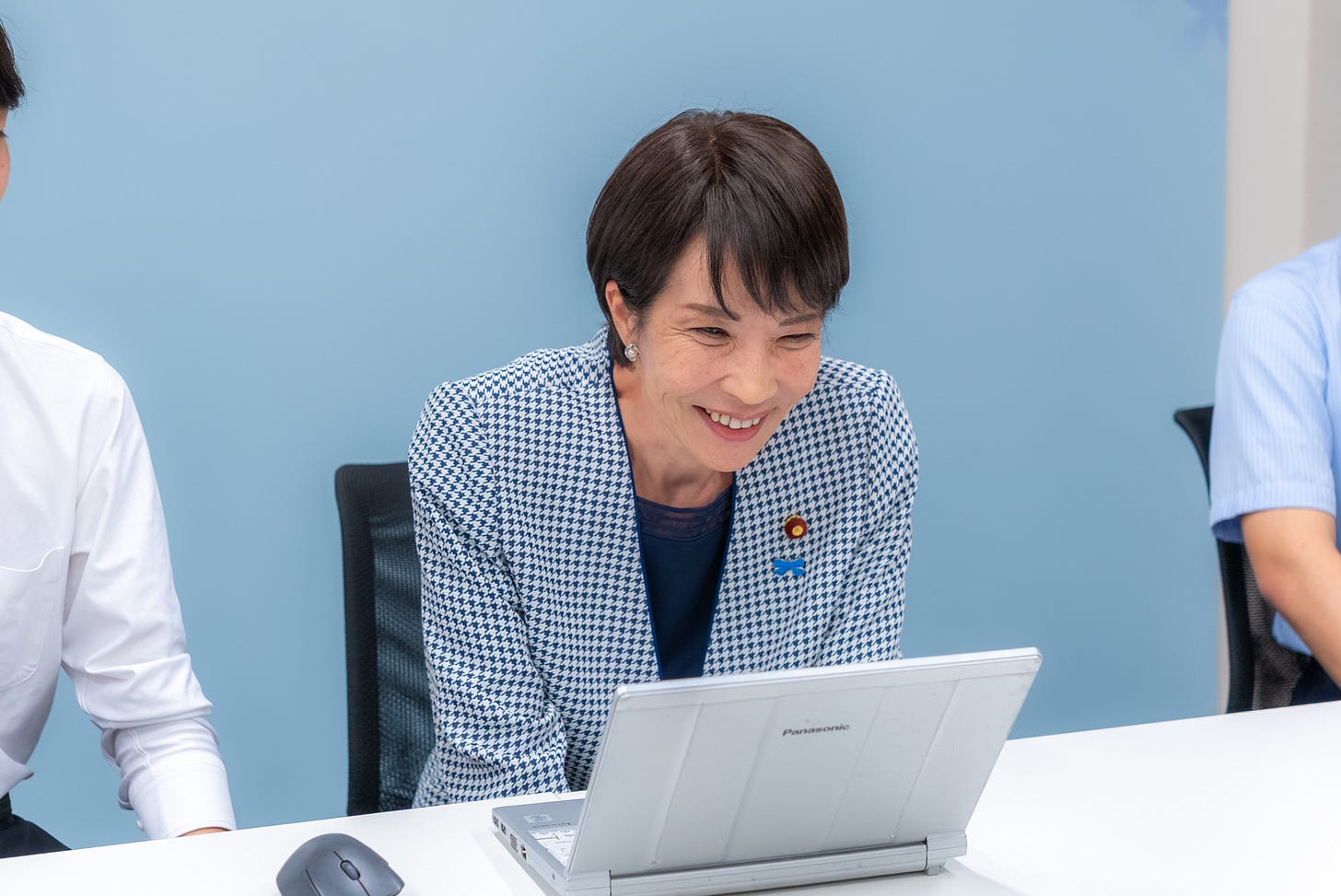

Yet despite the policy groundwork that has been laid, domestic headwinds may hamper actual AI uptake. Shigeru Ishiba, whose government pledged to make Japan “the most friendly nation for AI development and deployment in the world,” resigned as prime minister last month, and his successor, Sanae Takaichi, must navigate a coalition without a majority in the House of Representatives. During her campaign to lead the Liberal Democratic Party in September, Takaichi launched an AI chatbot based on her writings and social media posts for voters to interact with.

If the Liberal Democratic Party continues to struggle, it might shift focus to short-term survival tactics rather than a proactive, long-term AI strategy, says Carnegie’s Kushida. Yet Japan’s demographic crisis — particularly acute outside the big cities — isn’t going anywhere, creating sustained pressure for AI adoption.

“If we show the pain points and the potential upside of AI implementation, and if regional politicians can convert those into votes, then we have a political pathway to deploying this,” he says, adding that Japan could surprise the world with rapid AI adoption.

In the long term, the real test of Japan’s regulatory model, however, may lie in its global influence. Japan has already shaped international AI governance during its 2023 G7 presidency, when member nations agreed on voluntary conduct codes for advanced AI development. These encouraged developers of advanced AI to identify and mitigate potential risks, implement risk management policies and invest in security controls.

If Japan’s flexible approach proves successful, it could offer a model for countries seeking alternatives to regulatory extremes — through trust and adaptation rather than punishment.

This piece really made me think about Japan's fascinating 'third way' approach to AI. It makes me wonder if such a framework could truly scale globally, without a clear accoutability mechanism. So interesting!